Fish in the Bay – April 2019, UC Davis Trawls – April is baby fish month (Part 2).

Happy April part 2 (now a little belated)! I went trawling with the Hobbs team on three weekends in April … so, more info to share.

First a Correction: Eggs shown in the previous “Fish in the Bay” post were Jacksmelt eggs, not Pacific Herring. I received this note from Andrew Weltz at the CDFW office in Santa Rosa:

Jim, … I wanted to point out that these are not herring eggs. … they are likely jacksmelt eggs (these are larger than herring eggs and have that stretchy string that attaches them to substrate). Jacksmelt and herring spawning do overlap, but herring is earlier, and by April it would be very rare to see any herring spawn in SF bay. This year, our last recorded spawns were in mid-March.

Jacksmelt egg (and other) info (Tom Greiner, also at CDFW, provided the last two sources):

- This “California Fly Fisher” note from 2004 summarizes Jacksmelt life history, including spawning: https://www.calflyfisher.com/msgboard/viewtopic.php?t=300

- This 1929 “Fish Division of Fish and Game of California, Fish Bulletin,” documents Jacksmelt spawning and egg development in (mostly Southern) California: http://content.cdlib.org/view?docId=kt258001x6&brand=calisphere&doc.view=entire_text

- Japanese sushi “Masago” is “smelt roe.” But, Masago seems to be mainly Capelin Smelt roe, though roe from Longfin Smelt, Night Smelt, Rainbow Smelt, Surf Smelt, and/or Whitebait Smelt can also be used.

- Johnson C.S. Wang. 1986. Fishes of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Estuary … A guide to the early life histories. Tech. Report 9 (FS/B10-4ATR 86-9). Prepared for the IEP Study Program. (Warning – 680-page report with many baby fish pictograms!) https://www.usbr.gov/mp/TFFIP/docs/tracy-reports/other-ttr-2010-no9-fishes-sac-sj-estuary.pdf

- Johnson C.S. Wang. 2010. (illustrations by Rene Reyes)Fishes of Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta … A Guide to Early Life Histories. Vol.44 – Special Publication. (Good news! This report is a mere 411 pages.) https://www.usbr.gov/mp/TFFIP/docs/tracy-reports/tracy-rpt-vol-44-special-fishes-sac-sjr.pdf

Tom Greiner also shared a couple of observations about SF Bay Herring and gobies that I will follow up on as specimens become available:

- “Arrow and yellowfin gobies dominate the flats, whereas bay and cheekspot gobies are more common in deeper water. For small gobies the ‘spot’ is not a good identification character, but mouth size is smaller in cheekspots than arrow gobies.”

- Decades ago Tom observed: “… Young-of-Year (YOY) herring from Upper San Pablo and Suisun Bays were usually golden backed, whereas YOY herring from closer to central bay were typically blue backed. Green backed herring seemed to predominate in intermediate areas, such as lower San Pablo Bay and South SF Bay.” [Tom suggests turbidity or salinity, or both, as at least correlating, if not causative factors.

Folks! I greatly value all advice and educated opinions. I need all the help I can get!

1. Clams & Bugs of April

This is the dead “shell hash” from Macoma clams that we typically see in Alviso, Artesian, and Coyote Creek sloughs, particularly after wet winter flushing. The live clams are too deep in the mud to be caught by Otter trawling, so I can only crudely guess their relative abundance from shells we see. (A problem with shells is that they last a long time: decades, even centuries! Not a good way to assess current clam populations.)

In addition to typical Macoma shell hash, we picked up some live Corbulas and Corbicula shells at UCoy stations.

- Corbula are the brackish-to-saltwater invaders.

- Corbicula are the non-native freshwater menace. It is always worrisome to find these shells at the downstream end of Coyote Creek. If Corbicula shells are here, then these nasty little clams must be established farther upstream too.

Red Swamp Crayfish from Station UCoy2.

This is the second Red Swamp Crayfish, aka: “Louisiana Mudbug” seen in this area. The other one in March was freshly dead from presumed salt-shock (see February Fish in the Bay report: http://www.ogfishlab.com/2019/02/10/fish-in-the-bay-february-2019-uc-davis-trawls-longfin-alert-spawning-confirmed-for-2019/). I would guess that the recent wet winter helped foster both this non-native crayfish as well as the Corbicula clams mentioned above.

This young crayfish looks like good sturgeon food. Ghost shrimp of similar size and appearance are highly recommended as sturgeon bait. Lousiana Mudbugs are non-native, but extremely cute!

Exopalaemon shrimp. Exopalaemon and Palaemon shrimp have both been in egg-bearing mode for over a month now. As I look over older photos, I can see that both species have borne eggs over most of the warm seasons.

More Exos with eggs from UCoy2 on March 6th.

Exopalaemon shrimp populations have exploded over the past few years.

Two egg-bearing Palaemon shrimp; one red, one beige from UCoy2.

Palaemon shrimp. I continue to wonder why two female egg-bearing Palaemon shrimp, same size, same location, show different color. Both are nearly identical in every respect except that one is beige, the other is reddish. On closer look, the reddish shrimp appears to have a slightly larger carapace, perhaps. Also, the rostrum looks a little curved compared to the straight knife-like rostrum on the beige one.

Jar graph from April 6th.

Fucoxanthin Hypothesis: We sometimes see a red-orange or brown color that lyses from marine bug samples (brackish-to-salt water) when soaked in ethanol. Levi Lewis and I have speculated that the source of the red color might come from fucoxanthin pigment from diatoms (http://oceandatacenter.ucsc.edu/PhytoGallery/dinos%20vs%20diatoms.html), or from larger organisms that consumed diatoms. Could it be that Palaemon shrimp turn redder in saltier water for this reason?

In the “jar graph” above, the jar representing station Coy1, the most downstream mysid net sample, did show the ethanol-induced red-orange color again on April 6th. However, beginning and end-of-trawl salinity readings at all four stations were similar or completely overlapping. There was no salinity correlation based on these readings on this particular day.

… Investigation continues.

BTW: Jim Hobbs coined the name “Jar Graph” last Sunday. Henceforth, it will be an occasional feature in Fish in the Bay blog posts.

Vivid tomato-red Palaemon shrimp seem to be less common compared to last year. That might support the “Fucoxanthin Hypothesis.” Salinities at all station are lower so far in 2019 which would affect Palaemon diets and/or metabolism.

Two greenish Palaemon from Dump Slough.

Green Palaemon! I could swear Palaemon look generally greener and more clear-bodied this year. These two from Dump Slough look particularly green.

Reddish Palaemon! Two or three of these Palaemon look slightly reddish at this downstream station. None look as green as those from fresher Dump Slough.

Another batch of shrimp and mysids from Coy1.

The photo above shows groups of young Crangon, Mysids, and Palaemon shrimp.

- I believe these young Crangon are the result of the Great Crangon Brooding Migration of 2018/19 that we observed from late November through February or early March.

- Palaemon at this station again generally appear a little orangish. One stands out as a classic Tomato-red Palaemon.

Crangon shrimp. Many of the young Crangon look like the C. nigricauda, or black-tail variety, particularly at fresher upstream stations.

I don’t recall seeing any egg-bearing black-tail Crangon last winter amongst the many thousands of C. franciscorum (regular Crangon) in this area. It makes me wonder if black-tailed and speckled might be the normal appearance of juvenile C. franciscorum.

Male Harris Mud Crab from UCoy2.

Male Harris Mud Crab from UCoy2.

Harris Mud Crab. The narrow abdominal flap on the belly of this crab tells us he is a boy crab, if I am not mistaken.

Dragonfly nymph?

Dragonfly? Another sign of good creek flushing. This freshwater inset larva was caught at station UCoy2. It is probably a dragonfly nymph. I do not know insect nymphs well, so damselfly nymph may be another possibility.

2. Advanced Corophium & Gammarid Studies.

Corophium.

I made this Corophium anatomical diagram a couple of months ago to help me remember the names of all the different types of legs.

The Latin leg-naming convention is roughly similar for all crustaceans of the Malacostraca class (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malacostraca). This includes amphipods, isopods, and decapods (crabs, shrimp, and lobsters). Altogether, Malakostraca encompases most crustacean bugs of the world with 10 or more legs.

Corophium and all the other bug-like Malacostraca animals have around 20 body segments divided amongst the head, thorax, and abdomen. Most throrax and abdomen segments have a dedicated pair of legs. PLUS: the five head segments collectively have two pair of antenna and additional pairs of mandibles … to the best of my understanding.

I am still slowly getting acquainted with all the leg names. And, I continue to grapple with the concept that the giant front “legs” on a Corophium are actually 2nd antennae. They not legs at all, even though they are muscular and used for crawling in addition to sensing.

Corophium Couple. I had read that male Corophium have larger 2nd antennae than females. This pair appears to confirm that. In this case, the female is bearing eggs in her marsupium (abdominal brooding pouch).

Male Corophium: at around 8 millimeters in total length (body + antennae), this guy is a monster!

Female Corophium: smaller, with more delicate 2nd antennae.

By comparison, the egg-bearing female didn’t quite reach 6mm with antennae fully stretched out. Also, notice how much smaller and delicate her 2nd antennae appear compared to her body.

This is another Corophium pair caught further downstream at station Art3. This female did not appear to have eggs. She shows much smaller 2nd antennae compared to the nearby male.

Both Artesian and Alviso Sloughs are Corophium hot-spots. I presume this is because of the constant flow of enriching nutrients that, in turn, feed blooming phytoplankton and microscopic animals upon which corophium feed.

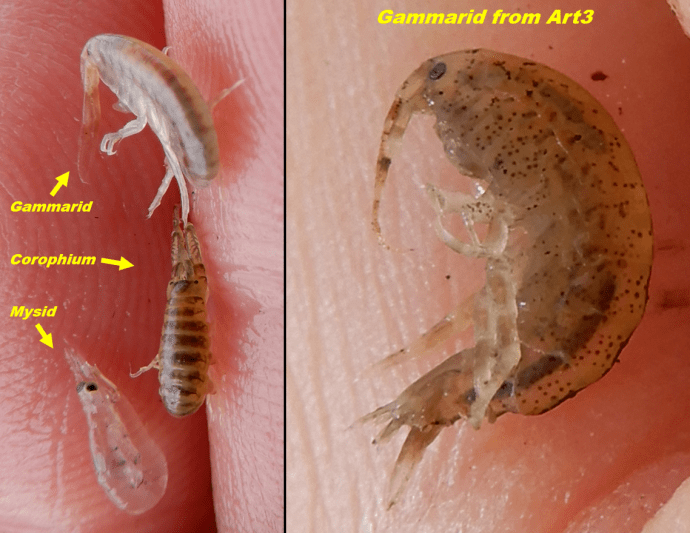

Gammarid.

Gammarids are the other bottom-dwelling, multi-legged bugs we commonly see in the sloughs. They are distantly related to Corophium. “Gammarids,” aka “Scuds,” tend to be larger than Corophium and have smaller 2nd antennae compared to body size.

Until 2003, both Gammarids and Corophium were classified as part of Gammaridae family: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gammaridae. Then, they were reclassified as members of the Corophiida infraorder: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corophiida. But after 2013, both Corophium and Gammarids have been regrouped under the Amphipod suborder called “Senticaudata.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Senticaudata.

In other words,

- Gammarids and Corophium are somehow related to each other, and

- Researchers far more dedicated and experienced than me are still figuring out where these tiny critters fit on the tree of life!

I have not yet caught enough Gammarids to be able to determine sex yet.

3. More Fish

Baby fish from the mysid net on April 6th.

Baby fish. Based on additional Jar Graphs assembled later in the month, I surmise that we reached “Peak Baby Fish” in mid-April. But, as shown above, we were seeing clear signs of the 2019 fish baby boom on April 6th.

Shiner Surfperch at Coy1. This Shiner was visibly pregnant. She has several to a dozen babies near ready for birth. (If you recall, Shiner’s are livebearers. They do not lay eggs.)

Levi Lewis with White Sturgeon from Coy1.

White Sturgeon. Levi Lewis is shown holding the White Sturgeon we caught at the end of the day. Pat Crane is using the Secchi stick to get a quick length measurement. This fish was 1.1 meters, or 43 inches, (total length), which might be just over the 40-inch (fork length) lower slot limit over which a sturgeon can be legally taken.

4. Baby Seals

Calaveras Point Seal Colony on April 13th.

Easter Seals! As we slowly dragged the 20mm larval net at Station Coy4, I took another close telephoto look at our seal colony. (Reminder, all that mud, and much more, accumulated since 1990!)

The seals looked more cinnamon red than usual. Recent rains might have cleaned them up.

We noticed some seal pups for the first time. Evidently, pups are not red.

Two more seal pups showed up on our second pass.

Three seal pups! When we passed by about 20 minutes later, two more pups showed up. The few gray adults must be young or new to this area. The conventional wisdom is that red seals accumulate iron compounds or other pigmenting material over time.

5. Baby Eagles

Milpitas Bald Eagles – Year 3

Easter Eagles! I felt inspired to construct a new Eagle mini-poster based on recent Facebook postings by Milpitas bald eagle fans.

- Photographer Key: AB = Alfred Bruckner, CD = Cudake Dee, RL = Ron Lam

Longer story. A bald eagle pair showed up in the Milpitas area in late-2016. I first noticed them as a bonded couple on January 4th, 2017. Shortly after that, they built a nest over Curtner Elementary School in Milpitas where the eaglet, named “Junior,” was hatched. Last year, the eagle couple raised two more eaglets: Lucky and Luckier. Facebook postings regularly document the parents bringing food to the nest: Stripped Bass, Squirrel, Duck, Coot, and, as illustrated above, stocked Trout from nearby Sandy Wool Lake.

Next time: Back to fish and bugs. I have more additional Jar Graphs to share. …

Previous Post

Previous Post