Fish in the Bay – March 2020: Spring Spawns – Part 1

I am social-isolating and self-sheltering to maximum extent possible. Yet another naturally-mutated virus popped up and potentially threatens to mow down our huge monoculture of a species. When has this not happened before, again and again, in evolutionary history? Personally, I am not fearful of the virus; just mindful that I do not want to spread it.

The Human Advantage: We understand infectious disease! We know about genetics! Think of all the medical science, food production infrastructure, power generation, sanitation, and all the rest that keeps us safe from being mowed down by wayward microbes. If we don’t have resistance, we can create it. It’s just another piece in the giant biological puzzle.

I am more inclined to look at the pieces I can touch and see in Lower South Bay. So, on to fish and bugs…

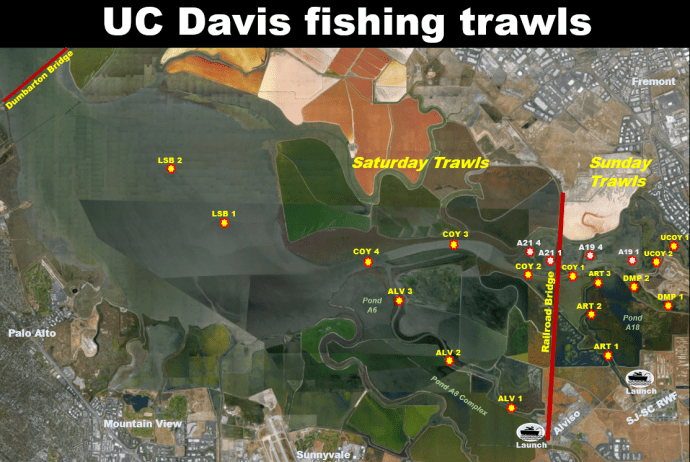

Trawl map.

Bay-side stations trawling results.

Upstream of Railroad Bridge.

Once again, more was going on this month than I can cover in a single blog-post. Here are some initial highlights:

- Ctenophores again.

- Evidence of spawning fish.

- Bay Gobies, Croakers and Shiners! What is going on?

- Halibut and Snail Eggs.

1. Ctenophore invasion continues.

Ctenophores at Alv2

Ctenophore invasion intensifies! We caught even more Comb Jellies this second month: almost 3,800 of them! (A typical monthly count is ZERO (0)!!! But, smaller blooms occur every few winters.)

These primitive-seeming, radially symmetric, diploblastic lifeforms were amongst the most advanced animals during the much earlier pre-Cambrian era – prior to about 550 million years ago. (Some sources claim they are triploblastic – having true organs in addition to true tissue – or maybe something in between!)

Sometimes we refer to critters like this as “Living Fossils.” They survived essentially unchanged from an earlier era because they are mega-successful throughout the ages. Why should they change? They are evolutionary winners swimming amongst the hordes of more complex organisms, like ourselves, that will certainly be nothing more than fossils long before Ctenophores go extinct.

Ctenophore close-up #1 – Ctenophore in the Photarium.

Ctenophores are little more than transparent jelly-filled beach balls with rudimentary digestive and reproductive systems inside. The eight rows of ciliated comb plates, or comb rows, form the outer seams of the ball. Running under each comb plate is a Meridional Canal. Male and female reproductive organs line these canals and gametes are dispersed out through gonopores in the comb rows from what I read.

This photo shows smaller filaments connecting the combs to the central digestive organs. I believe those are “Transverse” or “Adradial” canals.

Most species of Comb Jellies have long, sticky flagellar arms (tentillum) extending from Tentacular Canals. But, so far, I have not spotted any tentillum nor Tentacular Canals on our SF Bay variety.

Ctenophore close-up #2.

There are small clumps in this Ctenophores’ belly (center bottom) of the jelly. Could the clumps be semi-digested copepods? What are those reddish filaments on either side of the stomach? I need to find a book on Ctenophore anatomy.

2. A new generation of Lampreys, Herring, etc.

Pacific Lamprey in the tray.

Pacific Lamprey. Two of these boneless, jawless, 300 million-year-old “Living Fossil” (i.e. mega-successful) ancient fish were caught on Sunday at upstream stations.

Both Lampreys were in their “macropthalmia” or “juvenile” stage of life. I tend to refer to them as “teenagers.” In actuality, macropthalmia are between 3 and 7 years old. They have grown past their mud-dwelling larval, or “ammocoete” life-stage. Now with big eyes and teeth, they are on their way to the Pacific Ocean to grow big. Like Salmon or Steelhead, adult Lampreys eventually return to Coyote Creek for spawning and death. https://www.fws.gov/oregonfwo/species/data/pacificlamprey/documents/012808pl-factsheet.pdf

Good News! Although they still creep me out a little, Lampreys are an undeniable sign of beneficial FISH SPAWNING (SPWN) and FISH MIGRATION (MIGR) in Coyote Creek as referenced in the San Francisco Bay Basin Plan: https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/rwqcb2/water_issues/programs/basin_plan/docs/basin_plan07.pdf (See pages 12-14 – However, note that the Basin Plan does NOT specifically mention Lampreys!)

Creek habitat and flows must be at least marginally good if we are seeing Lampreys again!

Young Pacific Herring

Pacific Herring. 37 young Herring were caught this month. That is a decent haul for March, but far short of our record of 338 in March 2018. Hopefully, we will see a few more in April before these young head out to sea.

Pacific Herring from Pond A21 arranged by size. Note greenish dorsal color of bottom (oldest) Herring.

Unfortunately, as you may have read elsewhere, Pacific Herring are not doing well up and down the west coast of North America: https://www.sfestuary.org/estuary-news-where-have-all-the-herring-gone/

Bay Pipefish from DMP2.

Bay Pipefish. One particularly fat (222 mm) Pipefish was found at DMP2. I believe she was a female because I could not detect a belly pouch.

Close-up of the big female’s head.

Close-up of the big female’s head.

Like their seahorse cousins, Pipefish bodies are hard and well protected by a dermal skeleton, but their gills are small compared to body size. They cannot endure being out of water for long, so examination time is very brief. Then, they must be returned to the marsh.

Young Staghorn Sculpin at Art3

Pacific Staghorn Sculpin. All the 133 Staghorns we saw in March were young to larval in size. We always catch more big adults from around November through January at latest. Babies show up shortly thereafter. Dry years tend to favor them in this area.

Baby staghorn (top), young staghorn (bottom) from UCoy1.

3. Blast from the Distant Past: Shiners, Croaker, and Bay Gobies.

“Back to the Future” meme – image courtesy of Universal Studios.

For a second month, we caught baby Bay Gobies! This is the fish we had not seen since 2012 in Lower South Bay, aside from two or three rare oddballs. To top it off, 3 Shiner Surfperch and 3 White Croakers were caught as well. Together, these three species were among the most common Otter Trawl catches in the 1980s.

Two Shiners from Coy4

Shiner Surfperch. We still catch Shiners each year. But, numbers have fallen from “common” a few decades ago, to several dozen per year in the early 2010s, to less than 20 per year after 2016. What is pushing them out of Lower South Bay? Is it a good trend, or a bad trend?

White Croakers were a bigger surprise. Like Shiners and Bay Gobies, Croakers were commonly caught here at least until the 1980s. But since 2010, only 12 were found in LSB trawls, never more than two in any given YEAR. This month we caught three!

Bay Goby (left) meets White Croaker (right) at Station Alv2

Granted all the Croakers, like the Bay Gobies, caught this month were babies. This may indicate more of a freak event than a trend at this point.

… Nor can we be sure that Croakers and Shiners are a good thing down here. Always remember that the three sewage treatment facilities that discharge treated wastewater into Lower South Bay (Palo Alto, Sunnyvale, and San Jose-Santa Clara) upgraded to tertiary treatment in 1979 and 1980. I am NOT willing to say that fish populations were yet completely healthy by the mid-1980s when Marty McFly & Doc Brown made their first time-travels. If anything, the Bay is cleaner now: very little ammonia and far less metals contamination is discharged according to published data.

Baby Bay Gobies from LSB1

Bay Gobies. 26 baby Bay Gobies were caught in March. Bay Gobies are unambiguously native to Lower South Bay, so their presence should be a good sign. On March 7th, we found them at most stations from Alviso Slough out to the middle of Lower South Bay. What is going on here?

More baby Bay Gobies from LSB1

Last month, we were so unfamiliar with Bay Gobies that we had to consult a CDFW expert for identification.

Special shout-out to Brian Jones, Senior Lab Assistant, Native Fishes Unit, Interagency Ecological Programs Bay-Delta Lab. Brian identified our baby Bay Gobies from photographs!

4. Two of our favorite Flatfishes.

Three young Halibut at LSB2

California Halibut with Crangon. So far, 2020 looks to be as good a year for Halibut as last year. Not a great year like saw in 2015-2016, but still good.

One big Halibut. We caught another very big halibut for Lower South Bay: 520mm, or 20.5 inches “standard length” (e.g. not counting the tail). Big guys and gals like this one usually migrate further north to Central Bay. They are legal to catch and eat at 23 inches. They are both vicious & delicious! https://wildlife.ca.gov/Fishing/Ocean/Regulations/Fishing-Map/Central

Micah shows off big Halibut from Coy4. Watch out for those teeth!

\

English Sole with parasite of the month, Coy3.

English Sole. As I mentioned last month, English Sole parasites are not really my thing.

Since then, Calvin Lee, a biologist with ICF, emailed me that last month’s featured parasite was protozoan “X-cell disease.” Calvin studied that parasite in SF Bay English Sole as his master’s thesis! https://sites.google.com/site/rtccohenlab/colleagues-collaborators/lab/calvin-lee

Close-up: Nasty parasitic tumor on English Sole.

Well folks, … there are plenty of different types of English Sole parasites; at least 29 of them from what I’ve read. Nearly all English Sole we catch have visible parasites. This one could be another X-cell tumor, or something else. We have the experts! We have work to do!

5. More Mud Snail Eggs.

Eastern Mud Snails and eggs at Coy4. Once again for a second month, we saw an enormous number of mud snail eggs. We don’t enumerate the egg capsules or eggs, but I know it was a lot.

Mud Snail eggs seemed to be on every type of hard or firm substrate. All of these photos show egg capsules on red algae, but the capsules were found on rock, shell, and even other mud snails. I do not yet know how common or rare this Mud Snail egg-explosion may be.

6. A note about studying Shad Colors

Threadfin Shad (top left) & American Shad (bottom right) from Pond A21.

Threadfin Shad & American Shad numbers are still good, but not exceptional. I only feature them here to comment on evaluating Shad colors.

Dorsal colors of shimmery fish like these are complicated by their surface sheen. Light angle and intensity are critical. Threadfins seem to have more reflectivity that appears as a purplish sheen. At the wrong angle, the sheen completely obscures the deeper dorsal color.

Threadfin Shad, below, and in front of, American Shad in these two photos.

Same fish, different angles. By tilting the fish relative to ambient light, the forest-green dorsal color (Pantone 17-0230) becomes clearly visible. The deeper dorsal color, not the sheen, of these attractive fish correlates closely with salinity.

… That’s all I can squeeze in ATM, but there is much more to discuss about Shrimp, Bat Rays, Anchovies and other March catches in another post.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post