Fish in the Bay – May & June 2020, part 1: Crangon Shrimp Recruitment Explosion.

Wilson Xieu, junior specialist at the UC Davis Otolith Geochemistry & Fish Ecology Lab, joined the trawls in May. Photo my Micah Bisson.

Folks, Bad News: due to COVID-19 transmission concerns, I was unable to join the UC Davis fish and bug trawls in May. The crew did their best to photo document the catches on cell phones. Alas, photo quality suffered.

Good News: COVID concerns were alleviated enough by June to allow me to once again join the boat for more photo documentation. For this report, May data tables are shown, but almost all photos were taken during the June 13-14 trawling weekend.

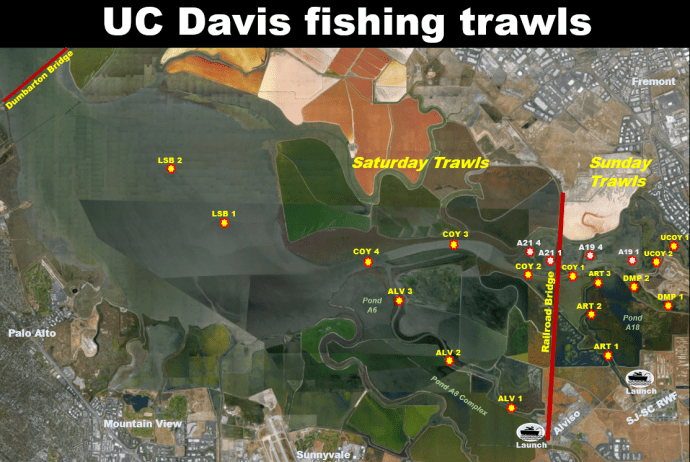

Trawl map.

Bay-side stations trawling results.

Upstream of Railroad Bridge.

May monthly data is shown in the tables above. June data has already been collected; I will show those tables in the next post.

This discussion will cover a mash-up of both May and June discoveries with focus on the massive Crangon shrimp explosion:

- Biggest Crangon Shrimp Recruitment EVER!!! (Granted our data only goes back a decade; with good comparable data only back to 2014.)

- Dungeness & Decorator Crabs: these usually rare odd-balls in LSB are not so rare this year.

- A couple of baby leopard sharks.

The next installment or two will focus on other interesting events.

- Halibut, Tonguefish, & Striped Bass bounce back.

- Anchovies “gold-up” and “brown-up” for summer.

- As expected, Staghorn Sculpin are showing up & Prickly Sculpin disappeared with increased salinity.

- Baby Fish Month came late: Yellowfin Gobies and Top Smelt exploded in June.

- California bulrush continues to flourish in Pond A19.

- Maybe some more stuff.

1. The Great Crangon-COVID Recruitment Explosion.

Young Crangon (C. franciscorum), like these caught in Pond A21 on June 13th, were found at all but the furthest upstream stations in both May and June.

Crangon Explosion in May 2020! The Crangon trend line is shown in red, Palaemon and Exopalaemon shrimp are indicated with brown and blue trend lines, respectively. (Year 2014 shrimp tallies are highlighted in yellow because trawl durations and station locations were slightly different. The data is otherwise comparable in terms of Catch Per Unit Effort – CPUE.)

(The entire Lower South Bay trawling data series goes back to 2010, but with many more breaks in the series and less consistent station locations prior to 2014.)

A tubful of shrimp: 10,300 Crangon at Station Coy2 alone on May 16th!

25,331 Crangon were caught in May! Another 12,353 were caught in June! These are fantastic Crangon catches. But, will this last? (BTW: all Crangon were released after counts.)

The shrimp scene at LSB1 on June 13th: Young Palaemon (translucent pinkish/tan) and Young Crangon (sandy brown) plus some mature gravid (berried) Palaemon.

Why did Crangon populations explode now? At first blush, I thought this Crangon explosion might have resulted from COVID-19 shut-down of human fishing and other activities. That would be a great story. But, notice that Palaemon & Exopalaemon shrimp numbers did NOT simultaneously rise. Also, Crangon counts were very good in February and March, prior to the COVID-19 disruption, so some more general condition may have stimulated Crangon recruitment this past Spring.

Decorator Crabs. Two more baby Decorator Crabs were caught in May and again in June.

Recall that we saw an unprecedented Ctenophore explosion in February and March. There seems to be a general invertebrate explosion event going on in the Bay – at least among the more marine species.

Dungeness Crabs. Two Dungeness showed up at station Alv3 in May. Another eight were caught at three stations in June. Perhaps even more unusual is that small shore crabs, i.e. Oregon Mud Crabs (Hemigrapsus oregonensis) and Harris Mud Crabs (Rhithropanopeus harrisii), that are occasionally present, and were quite common here years ago, have not been seen so far this year. Something is shaking up Crab World!

NOTE: It is difficult to determine sex when Dungeness Crabs are so young. At first, I was excited that all of the young ones caught in June appeared to have narrow aprons indicating “male.” However, Will White sent me a link to an Alaska Dept. of Fish and Game photo guide via Facebook. http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=dungenesscrab.photogallery&number=6

We now tentatively identify a few of the baby crabs as female. Had they all been male, it would have focused investigation into whether Dungeness could also be “protandrous hermaphrodites” or “sequential hermaphrodites” like Crangon and some isopods (see discussion further below). Luckily, we do not have to go down that path for now.

Could cold ocean upwelling off the coast be causing marine invertebrate explosions in the Bay?

- Paul Rogers reported in the San Jose Mercury News that the largest numbers of Blue Whales in over a decade were grazing krill off the Farallon Islands in mid-June: https://www.mercurynews.com/2020/06/18/amazing-dozens-of-blue-whales-spotted-off-northern-california-coast/

- Blue whales, krill, and cold ocean upwelling also reported by Bay Nature: https://baynature.org/2020/06/16/a-possible-record-number-of-blue-whales-visit-the-farallones/

- The same Blue whale invasion reported in the Point Reyes Light: https://www.ptreyeslight.com/article/blue-whales-converge-farallones-where-eating-good

Coincidence? … I think not!

2. Advanced Shrimp Studies – May through June 2020

A somewhat representative sample from LSB1: Young Crangon, mature palaemon, and young Palaemon on June 13th.

We saw a distinct Crangon gradient in March: Darker Black-tailed Crangon (C. nigricauda) predominated at Bay-side and deep Bay stations. Brown-tailed Crangon (C. franciscorum) were generally more abundant farther upstream. Most of the few thousand Crangon caught at the Lower Coyote Creek stations were adult-sized.

By May, the overall Crangon scenario had flipped. Vast numbers of small Crangon flooded the main stem of Lower Coyote Creek (Stations Coy1, 2, 3, 4, and Alv3). This population explosion persisted through June.

In June, Crangon at all stations tended to be small and brown-tailed. However, a number of small Black-tails (or at least darker tails) were also present.

Deep thoughts – about Crangon:

- Since late 2018, we observed two annual Crangon migrations in which gravid, egg-bearing, females (professional shrimpers call these “berried” females.) swim upstream to release their broods between around November through March. This is consistent with Crangon literature.

- Following brood release, adult females reportedly retreat back to the saltier Bay. Some sources say they may swim as far out to sea as the Farallon Islands.

- As waters warmed up each Spring and Summer, tiny young Crangon flood the system. These have been growing in fresher marshes since brood release. I suspect that both C. franciscorum and C. nigricauda recruit in these local sloughs – the proportions of each probably reflects year-by-year ocean climate trends, e.g. ENSO cycles and prevailing sea surface temperatures. A similar pattern shows up CDFW data collected further north in Central-South San Francisco Bay. See Fish in the Bay – October 2019, Part2, subsection #3, “Shrimp Wars” for full discussion: http://www.ogfishlab.com/2019/10/06/fish-in-the-bay-october-2019-uc-davis-trawls-part2-big-fish-in-a-little-pond-plus-a-shrimp-update/

- I discovered a fair amount of literature indicating that many, if not most estuarine Caridean shrimp species, like Crangon, are either “protandrous hermaphrodites” or “sequential hermaphrodites.” Therefore, these young Crangon should all be males that transition to female after a year or so. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sequential_hermaphroditism

- Apparently, a lot of estuarine crustaceans have crazy sex cycles. Usually, they are born male, mate, and then become female and mate again. Some parasitic isopods do this too: See Fish in the Bay – January 2019, subsection #2 “Isopod” discussion about Cymothoida: http://www.ogfishlab.com/2019/01/19/fish-in-the-bay-january-2019-uc-davis-trawls-parasite-paradise/

This continues to blow my mind.

Young Tiger-striped C. nigricauda(?) from LSB1.

Young Black-tails (C. nigricauda) don’t always express a “black tail.” This is the proof: the young Crangon, shown above has white “tiger-stripe” markings seen in many C. nigricauda in February and March. However, the tail is only slightly dark, not black. I am certain this one is a Black-tail.

Palaemon Shrimp (Palaemon macrodactylus). Palaemon in saltier parts of the Bay are translucent with a slight pink or orange hue which occasionally turns deeper red in some of the older gravid females.

7,290 Crangon at Station Coy4 on June 13th!

Crangon: young-of-year recruits. The majority of Crangon caught in both May and June were small young ones.

Protandrous Hermaphrodites. A few months ago, I reported that Crangon may be protandrous hermaphrodites. I am revising that conclusion based on literature review: Crangon franciscorum ARE protandrous hermaphrodites, and Crangon nigricauda likely are as well.

Many species of Caridean shrimps experience protandry: start life as males then convert to female. Apparently, several examples are well known. This means that these little Crangon may be all male.

- Definition of protandrous hermaphroditism: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/321494624_Protandrous_Hermaphroditism

- Correa and Thiel (2003), “Mating systems in caridean shrimp (Decapoda: Caridea) and their evolutionary consequences for sexual dimorphism and reproductive biology.” This paper gives an excellent explanation of some of the weird sexual life cycles of Crangon and other shrimp. http://www.bedim.cl/publications/Correa&ThielRCHN2003.pdf

- Maria A. Gavio, et al (2006) proposes that Crangon franciscorum exhibit “protandry with primary females.” Under that system, most shrimp start as male and later switch to female. BUT some, the primary females, start life as female and remain female. https://academic.oup.com/jcb/article/26/3/295/2670414

- A small library of papers discussing “sexual behavior in shrimp” is linked here: http://www.bedim.cl/crustacean.htm

Gravid female Palaemon from Station Coy4. Mix of gravid female and young pinkish-translucent Palaemon from Coy4.

Palaemon shrimp. Both Palaemon and Exopalaemon shrimp release broods over a longer period during the warm months, and we are seeing increased numbers of gravid females now.

An odd thing we have noticed about gravid female Palaemon: some are big, others are uniformly small. It must reflect some feature of their life cycle. Both large and small gravid female Palaemon were caught at Coy4. At station Coy1, all gravid females were midget sized – as discussed further below.

My first guess was that Palaemon could also be protandrous hermaphrodites. Midget-sized females may have more recently experienced sexual transition. However, Correa and Theil (2003), linked above, indicate that this is not correct: “…there are no reports of any kind of hermaphroditism for Palaemonidae despite the fact that many species present sexual dimorphism with smaller males (Berglund 1981, Omori et al. 1994, Bauer & Abdalla 2001).”

Furthermore, Correa and Theil (2003) states that: “… fecundity in females of all caridean species (and crustacean females in general) is positively correlated with female body size.” … Amongst Caridean shrimp, adult females are generally larger, never smaller, than the males. Midget gravid female Palaemon shrimp should be rare and an adaptive disadvantage. Yet, here they are! I have no explanation for midget-sized gravid female Palaemon at this point.

Stations Coy3, Coy4, and Alv3 are all near the junction of Lower Coyote Creek with Lower South Bay. Salinity fluctuates wildly with the tides. Nutrient-rich river and creek water meets the Bay around this location. And, this is where salt-water tolerant shrimp tend to congregate most of the time.

In both May and June, Crangon vastly outnumbered Palaemon at these stations.

Palaemon at Alv3. At this station, at least several gravid females were conspicuously smaller than most of the other non-gravid Palaemon. Again, this is strange. Shrimp literature clearly informs us that females should generally be larger amongst Caridean species. Some of these Palaemon are not following that rule.

Crangon, Palaemon, and Exopalaemon shrimp at station Coy1.

Shrimp at station Coy1. Station Coy1 is about two and a half miles farther upstream in Lower Coyote Creek. At this location, Exopalaemon shrimp (Exopalaemon modestus) show up consistently.

In photos above and below, I attempted to portray representative samples from the 1052 shrimp caught at Coy1 in June: 577 Crangon, 170 Palaemon, and 305 Exopalaemon.

Palaemon at Coy1: Nearly all Palaemon at this station were gravid females. On top of that, they were uniformly midget-sized. We do not measure shrimp lengths, so this is a qualitative observation.

Exopalaemon at Coy1: Clear-bodied Exos appear to be all adults. Many were berried females. My guess is about 20 percent seemed to be carrying eggs. (Gravid female Exos do appear to be as large or larger than the others, in conformance with Caridean shrimp rules.)

Exopalaemon closeup at Coy1 – two gravid females.

Exopalaemon close-up. Exopalaemon are the most recent invader in this area; first confirmed here in 2012. … They are an attractive shrimp!

Exopalaemon shrimp at upstream stations in June.

Exopalaemon shrimp prefer fresher water. Exos are more prevalent as we move upstream and into restored ponds.

Gravid female Exopalaemon (top) and Palaemon (bottom) side-by-side comparison.

Reminder: Though we continue to refer to them as “Exopalaemon,” they were reclassified as “Palaemon modestus” and members of genus Palaemonidae, per DeGrave and Ashleby (2013) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258446441_A_re-appraisal_of_the_systematic_status_of_selected_genera_in_Palaemoninae_Crustacea_Decapoda_Palaemonidae

Despite appearances, Palaemon macrodactylus and Palaemon modestus are somewhat closely related.

A mix of shrimp at station UCoy2 in June.

Station UCoy2 is the farthest upstream station along the main stem of Lower Coyote Creek before waters creek waters become consistently fresher. As usual, we saw a mix of shrimps there: young Crangon recruits mixed with older Palaemon and Exos. As Summer months progress, the numbers of Crangon should decline and numbers of Exos should rise – we shall see.

3. Leopard Sharks

Wilson shows off one of three baby Leopard Sharks caught in May at station Coy3. Shark lengths were 220, 228, and 236 mm.

Leopard Shark. Three Leopard Shark pups were caught in May and another one in June. In both months, these baby sharks were netted near the highest concentrations of Crangon shrimp.

Leopard Shark netted at Station Coy4 in June. Length: 250 mm

Leopard Sharks eat a lot of different bottom-dwelling critters, like polychaetes, clam siphons, shore crabs, and such. I would guess that a shark this size COULD consume Crangon as a significant part of its diet.

Graphic provided by Jon Kuntz.

Jon Kuntz provided a graphic from one of his presentations on Leopard Shark diet in San Francisco Bay. In that gastric lavage study, shrimp comprised only 3 percent of shark diet.

- I believe the graphic reflects results from this Hobbs et al. Leopard Shark study: https://www.southbayrestoration.org/sites/default/files/documents/011615_leopard_shark_chapter_final_report.pdf

- A 2014 Bay Nature article describes the study and includes a short video showing the gastric lavage procedure.

- Leopard Sharks are generalists. I speculate that a young Leopard Shark would happily eat more Crangon shrimp and fewer shore crabs given the numbers seen in June. … Further investigation is needed.

4. Pelicans on break.

Pelican Time-out. A pair of American White Pelicans loafing at the edge of the mudflat near Alviso Slough as we motored to Station Coy4.

White Pelicans dotted the shoreline as we counted shrimp at the various stations on June 13th.

Enough about shrimp for now. Even though Crangon are probably the most important species in the Bay (Anchovies may be a close second), fish investigations continue. I will submit additional fish information and the June data tables in a following report.

Previous Post

Previous Post