Fish in the Bay – January 2021, Part 2: La Nina Skies; shrimp, parasites, and more.

Sunrise near station Coy4 on January 30th, 2021

I had some odds-and-ends left to report from the January trawls. Beautiful sunrises and sunsets throughout January and February distracted my attention. A rainless winter is odd enough for the SF Bay Area. Dazzling dawns and dusks illuminating low stratus clouds stood out like a red flag.

1. La Nina

This has been a classic La Nina season: dry and cool. This oddly dry weather might have finally broke on the second week of March, but it wiped out what should have been our rainy season. By definition, ENSO represents a change to Sea Surface Temperature (SST) in the central equatorial Pacific.

- La Nina (the negative phase of ENSO): Strong tradewinds near the equator blow warm surface water towards Asia and Australia. This results in cool upwelling off the coasts of the Americas. The upwelling circulates nutrients and stimulates fish production, jellyfish, and kelp forests on this side of the Pacific.

- El Nino (the positive phase): Weak tradewinds cause warm surface water to stay put. Warm SST in the Eastern Pacific suppresses upwelling. This is not so good for local fish production, albeit the warmth draws southern fishes northward, eg. anchovies, squid, California Halibut, and White Sea Bass. https://wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/Marine/El-Nino#26072343-how-does-el-nio-affect-ocean-fishing

- Classical El Nino/La Nina measurement was judged by sea surface temperature at different points along the equatorial Pacific Ocean. https://climatedataguide.ucar.edu/climate-data/nino-sst-indices-nino-12-3-34-4-oni-and-tni

- Nowadays, various atmospheric pressure and sea surface temperature parameters are used to assess the strength of a given El Nino or La Nina event: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/why-are-there-so-many-enso-indexes-instead-just-one

- Strong El Nino 2015: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/2015-state-climate-el-ni%C3%B1o-came-saw-and-conquered

- Strong La Nina 2010-2012: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2010%E2%80%9312_La_Ni%C3%B1a_event

Winter 2020/21 has been both cool and dry. The combination of dryness and coldness initially made me think that we might be experiencing a Super-Duper Strong La Nina this year. But, the El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) indices pointed to only a moderate (cool sea surface) La Nina. NOAA’s La Nina 2020/21 assessment: https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/lanina/enso_evolution-status-fcsts-web.pdf

- Further afield, a record-breaking cold snap swept down across North America from Alaska to northern Mexico in mid-February. https://www.cnn.com/2021/02/16/us/record-cold-weather-us-trnd/index.html

- Another report from weather.com https://weather.com/safety/winter/news/2021-02-14-record-cold-temperatures-plains-midwest-february

- La Nina alone can’t cause deep freeze across North America. Something else is going on!

The cold Arctic blast across North America on February 12th.

Arctic Oscillation! The extra factor is the Arctic Oscillation (AO). (AO is also described, using slightly different sets of parameters, as the Northern Arctic Oscillation (NAO) or the Northern Annual Mode (NAM)). A number of researchers have begun assigning more weight to the AO/NAM as a predictor of weather in the Northern Hemisphere. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arctic_oscillation

- Like ENSO, which cycles between warm/El Nino and cool/La Nina phases, the AO ranges from “positive” – high sea surface pressure and generally warmer, to “negative” – low sea surface pressure and cooler. The 2020/21 season experienced a “double-whammy” of La Nina coinciding with a strongly negative AO.

- NOAAs monthly AO index history is here: https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/teleconnections/ao/

- ENSO and AO/NAM are independent of each other but not entirely disconnected. Both indices trend positive when global Tradewinds and Arctic winds blow strong and negative as winds weaken.

- A more recently described phenomenon of wintertime Sudden Stratospheric Warming (SSW) complicates this picture further still!

- See: Ayarzaguena et al. (2020) https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/25480 and

- Domeisen and Butler (2020) https://www.nature.com/articles/s43247-020-00060-z?fbclid=IwAR3g2HkN3xWL6TdDdRt1R_hVlkPCeLdK7FM_CkJUg9oGsk7aI3q175SvtHU

Weird weather caused me to waste far too much time diving down multiple climate-cycle rabbit holes: We can’t predict the weather, but with practice we still may learn to predict the fish and bugs!

2. A Trash Petition:

The South Bay Clean Creeks Coalition is circulating a petition to urge City of San Jose to enforce prohibitions against camping on creeks there. For several years the Coalition has been organizing creek cleanups that have picked up many thousands of tons of trash and debris. But, the trash keeps piling up faster than volunteers can remove it.

The problem is exacerbated by homelessness, mental illness, and general lack of concern for creek health. Meaningful prohibition of camping on the banks of urban creeks is just one step, but it is an important one. The Cities of Oakland, Sacramento, and Santa Cruz have already taken measures. It is time for San Jose to address the problem as well.

If you care about Bay Area creeks, consider signing the petition. https://www.change.org/p/south-bay-residents-advocate-for-a-san-jose-policy-for-no-camping-near-waterways

(Please note: Donations are NOT required – Donations offered on the change.org website go to change.org, not to the South Bay Clean Creeks Coalition.)

3. Shrimp Wars

Shrimp at Coy4 on January 9th – fewer Crangon, more Palaemon.

Crangon shrimp. January should be the high point of Crangon brooding season. In previous years we saw thousands of egg-bearing mamas by now. The catch continues to be thin this year. There were very few berried females in early January. Numbers of egg-bearers increased a bit as the month progressed, but it was still a very low count.

The overall shrimp tally from regular January trawls on the 9th and 10th was 1,427 Palaemon shrimp versus 1,162 native Crangon. The ratio was almost 1:1 at LSB stations but tilted in favor of Palaemon in upstream sloughs.

Egg-bearing Brown-tailed Crangon. We caught berried Brown-tailed females here and there, just not very many. These berried females were generally congregating a few miles upstream at stations Coy1 & Coy2 compared to station Coy4 last year. This may make sense if they actually seek freshwater to release eggs.

Berried female in Pond A21 on January 23rd.

Cold temperature triggers Crangon to migrate upstream each year. We know that freshwater aids recruitment of Crangon young, but lack of freshwater alone should not depress the number of berried females showing up in January unless the females actively seek freshwater for egg release. Do they seek low salinity?

The Crangon life-cycle is critical to this marsh ecosystem! If we don’t understand it, who does?

Brown-tail and Black-tail Crangon at LSB1 on January 9th.

Crangon nigricauda – the Black-tails. As usual, Crangon tails generally get blacker farther downstream in Lower South Bay.

- Crangon franciscorum are the “Brown-tails” that migrate upstream.

- Crangon nigricauda are “Black-tails” that like saltier water.

You can’t necessarily tell Brown-tails from Black-tails by naked eye. There is always a blurry gray or dark-brown region in between. (Legitimate identification may require a dissecting microscope and needless loss of Crangon life.) Let’s just continue to stipulate that Black-tails live in saltier water!

Crangon nigromaculata. “Blue-spot Crangon” are the saltiest Crangon of all. Once again, we caught Blue-spots at most stations in the main stem of Coyote Creek, even upstream to Coy1.

Blue-spot Crangon in Pond A21 on January 23rd.

Blue-spots only arrive in LSB in mid-winter while it is cold and still salty. In most years, we only see them at stations LSB1 and LSB2. We do not enumerate them, but Blue-spots appeared to comprise at least 10 percent of total Crangon at downstream stations this month. This is a big year for Blue-spots!

All three species of Crangon brood up with eggs around January. Unfortunately, Brown-tails seem to be getting squeezed out of much of their normally fresher water habitat this year.

Adult Palaemon shrimp caught at Coy1 on January 10th.

Palaemon Shrimp. Populations of these non-native and misnamed “Oriental Prawns” surge in drier years. They probably compete with native Crangon and vice-versa.

I suspect that Palaemon simply survive here when estuarine food production is lower. Over the several years we have documented, Palaemon numbers never topped 20,000 and were usually less than half that number. In contrast, Crangon franciscorum total numbers exceeded 60,000+ in the better years of 2014, 2018, and 2020.

Plus, Palaemon are not known to migrate out to the ocean. Palaemon shrimp represent a broken strand in the local food web.

4. Baby shrimp and fish

Baby Crangon are appearing in upper portions of Alviso, Artesian, Dump, and Coyote sloughs, so hope for the next generation is not completely lost. Many of these babies are no bigger than Mysids which suggests that they may be eagerly eaten by fish and birds that also feed on Mysid blooms.

Other babies are showing up in addition to Crangon. In past years, we usually noted March or April as “Baby Fish Months” largely owing to the explosion of young Yellowfin Gobies and Pacific Herring. However, our ability to identify these Mysid-sized babies improves each year.

Baby flatfishes. The first three English Sole of 2021 arrived in January along with several Speckled Sanddabs.

Many more baby flatfishes were picked up during Longfin Smelt trawls later in the month. These fishes often cannot be identified to species when they are small and transparent. English Sole, Speckled Sanddab, Diamond Turbot, California Halibut, and Starry Flounder are all common possibilities here.

Bay Gobies used to be common in Lower South Bay through the 1980s. They all but disappeared after 2012. Last year, we learned that three or four small dark dashes along the tail signify the Bay Goby when it is still very young and transparent. We counted 31 baby Bay Gobies in February and March 2020. Now, they are showing up again even farther upstream!

Young Chameleon Gobies were also caught in Longfin Smelt trawls near Coy3 in late January. These are common far out in Lower South Bay but rarely seen this far upstream. Like Black-tail and Blue-spot Crangon, high salinity is pulling the Chameleon Gobies further up into the marshes.

(Chameleon and Shimofuri Gobies are closely related cousins. Chameleons prefer marine salinity, “Shimos” like fresher water and are more common here. White margins on the anal and second dorsal fins, and near absence of spots under the jawline, indicate that the above fish is a Chameleon Goby.)

5. January is parasite month.

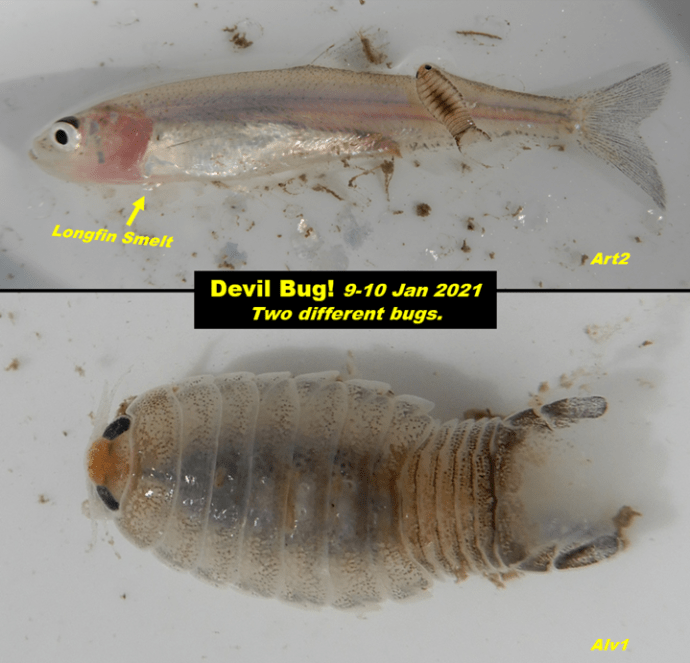

The Devil Bug. The “Devil Bug” is a Cymothoid isopod that attaches to the gills of American Shad and Longfin Smelt here. The bug is common all over the world and infects practically any type of fish with a big enough gill opening. We only see them in winter as the pelagic fishes return for spawning. I assume these bugs hitchhike in from deeper waters.

These parasites are protandrous hermaphrodites: they hatch as males then transition to females later in life.

The Devil Bug attacks an Arrow Goby at Art2 on January 10th.

The Devil Bug attacks an Arrow Goby at Art2 on January 10th.

Devil Bug experiment. By accident, I dropped an Arrow Goby into the Photarium with a small Devil Bug as we cruised down Artesian Slough. This goby is too small to host this bug, but it was interesting to watch the bug’s reaction.

The Devil Bug is an agile swimmer. It swooped and zoomed around the Arrow Goby, always aiming for the Goby’s operculum (gill cover). But, the bug was far too big for this tiny goby. The Goby was clearly not pleased with this attention. I dumped them both back into the slough after a few minutes of drama.

Bopyrid Isopods infect shrimp in a similar way. Large females crawl under shrimp carapaces and attach to gills just behind the shrimp’s head. The male isopods are tiny and attach themselves to the big female. These parasites seem to infest only the Blue-spot Crangon (C. Nigromaculata) here. I don’t recall seeing them in any other type of shrimp in LSB.

- There are many varieties of Bopyrid Isopod parasites. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bopyridae

- Jay (1989): According to this, and other sources, Bopyrid Isopods more often parasitize female shrimp. The isopod infects an intermediate copepod host as it matures. Interestingly, this study in Humboldt Bay found C. franciscorum to be the most infected amongst the three species of Crangon! https://www.jstor.org/stable/2425657?seq=1

Sea Lice! Lots of baby anchovies are getting tagged by these vampire “Caligidae copepods” from hell. Like the isopods, we see these bugs more often in winter. The parasites we found on Brown Smoothhounds and Starry Flounder a few months ago probably hitchhiked in from the ocean. But, but this particular variety is stuck to recently-hatched Anchovies that have not been out to sea. These Sea Lice could live their entire life-cycle in the local marshes.

- Morales-Serna et al (2016): Hundreds of species of Caligidae Copepods are distributed around the world. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23766808.2016.1236313

- Kim, Suarez-Morales, and Marquez-Rojas (2019): Similar sea lice near Venezuela are typically caught as free-swimming adults. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41208-019-00130-w

English Sole are rarely caught without some kind of internal or external parasites. Since we only ever see English Sole in winter, this fish alone is responsible for most of our January parasite surge.

Researchers have documented 29 different kinds of parasites on English Sole in Coos Bay, Oregon. With time and patience, I hope to someday photograph all 29.

I don’t know the identity of this pink-boil disease. It could be a different appearance of the protozoan “X-Cell disease” we have seen before, or maybe something new. As always, if anyone else is studying parasites in English Sole, contact me: these photos are for you.

Scoliosis is a spinal birth defect, not a parasitic disease, but this seemed like a good place to list it. In past months, I showed some rare examples in American Shad, Shimofuri Goby, and Inland Silverside. This month we found a bent Anchovy and a Longfin Smelt.

6. Big fish.

Anglers above. Big fish below!

Clear skies brought out the anglers in January. It was interesting to see all the recreational fishing boats at station Coy4 while watching underwater sonar scans of big Striped Bass and Sturgeon below.

Pro Tip: These big fish generally don’t bite when the water is really cold. Wait for the first warm day after the cold spell; then the bite will be on!

7. Drawbridge – the ghost town.

The ghost town of Drawbridge under the clear La Nina sky.

The Bay Area’s only ghost town is dissolving into the marsh. The roofs over two of the remaining sheds appeared to have collapsed this year.

Drawbridge is an interesting piece of early Bay Area history. Almost everything I know about it came from Ceal Craig:

- Ceal’s presentation. https://sfbws.com/sites/default/files/drawbridge/Drawbridge-slides-Ceal-Craig-2015-February.pdf

- Her book. https://sfbws.com/book-drawbridge

Closeup of Drawbridge’s disintegrating shacks.

But ecologically, it is an ugly history. Hunters were originally attracted here because the railroad line provided access to massively abundant ducks and marsh birds.

The rest of the tale is almost too predictable. The birds were largely killed off. The freshwater table dropped and made drinking water expensive to pump by the 1930s. Sewage, both here and nearby, killed fish and made the whole area smell bad. The local salt company leveed-off the surrounding marsh to create near-lifeless salt evaporators. The entire area subsided 2 feet as the underground aquifer dried up. Vandals periodically set vacant shacks on fire. The town became an uninhabitable nightmare!

The old Whitten Boathouse in Drawbridge, 10 Jan 2021.

It needs to fade away: this place is a fire trap! The birds and fish don’t need it. And, these structures are not really that old when you consider all the other old buildings we value in cities like Oakland, San Francisco, or San Jose.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post