Fish in the Bay – March 2021: La Nina Baby Fish Bomb.

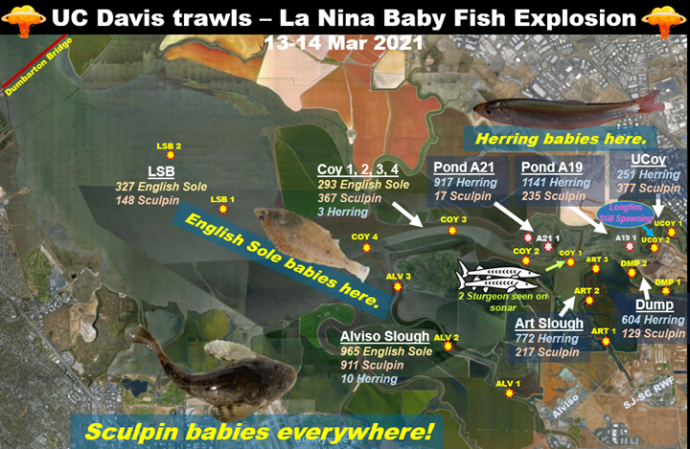

Trawl map.

We caught a lot of baby fish in March; more shrimp than normal as well. The Pacific Ocean La Nina/ENSO cycle could be responsible! … more below.

Bay-side stations trawling results.

Bay Gobies and White Croaker are again highlighted in red. Every spring we catch a few of these fish. They were common here a few decades ago.

Upstream of Railroad Bridge.

Salinities 12 ppt and less are highlighted in blue. Somehow, most Coyote Creek stations and the two stations upstream on Alviso Slough continue to show near single-digit salinities despite the lack of rain.

1. English Sole, Herring, and Sculpin Explosion.

Herring, Sculpin, and English Sole were caught in numbers we have not seen since March 2012! What is going on here?

- This winter season has been conspicuous for two factors: Lack of rain and La Nina-induced cool Sea Surface Temperatures (SST) along the coast.

- Rain didn’t cause this baby fish explosion … It must be La Nina!

Denise Colombano, Postdoctoral Fellow at the Berkeley Freshwater Group, referred me to a paper by Feyrer, Cloern, et al. (2015): “Estuarine fish communities respond to climate variability over both river and ocean basins.” The paper synthesizes 30 years of research history and Bay fish data against precipitation and NPGO/Pacific Decadal Cycle climate trends. It is a complicated read, but essentially, yes, the authors found correlations between certain fish species and guilds with changes in ocean conditions and river flows. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.12969

- Denise’s own work tracks fish nursery functions, albeit for different species, in Suisun marsh habitats in north San Francisco Bay. See Colombano, Manfree, O’Rear, Durand, and Moyle (2020): https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338794254_Estuarine-terrestrial_habitat_gradients_enhance_nursery_function_for_resident_and_transient_fishes_in_the_San_Francisco_Estuary

- A summary of the Colombano paper is provided in this Delta Stewardship Council report: https://www.deltacouncil.ca.gov/pdf/council-meeting/meeting-materials/2020-07-23-item-9-lead-scientist-report.pdf

Could La Nina and cool SST be a driving factor? These are three very different kinds of fishes. What could connect their life cycles to cool SST?

English Sole at Alv1.

English Sole hatch in coastal waters. The fry swim into bays and estuaries up and down the west coast of North America. In San Francisco Bay, they surf the tides to get to our southern marshes.

The connection between English Sole and La Nina cool ocean upwelling is well known. For example, see Nature Conservancy report by Hughes et al. (2014) “Nursery Functions of U.S. West Coast Estuaries…” p.97 “Abundance of larval and juvenile English sole seems to increase during cold-water regimes, especially in the southern portion of their range. Abundance of juvenile English sole in San Francisco Bay was very high during a cold-water regime that lasted from 1999-2011 (fish et al. 2013).” https://www.scienceforconservation.org/assets/downloads/Nursery-Functions-West_Coast-Estuaries-2014.pdf

English Sole at LSB1

We caught almost 1,500 Sole babies – all but 63 of them were downstream of the Railroad Bridge. Almost 1,000 of them were counted in Alviso Slough alone! Imagine how many must be rearing across the entire Bay.

(Also notice, many of these baby Sole do NOT have visible parasites. This was a welcome change.)

Young Pacific Herring and mysids from Pond A21 on March 14th.

Pacific Herring babies were almost all caught farther upstream. We caught over 900 Herring fry in Pond A21 and then 2,700 more at stations farther upstream along Coyote, Dump, and Artesian Sloughs.

According to Calif. Dept of Fish and Wildlife: “Pacific Herring are found throughout the coastal zone from northern Baja California on the North American coast, around the rim of the North Pacific Basin to Korea on the Asian coast. In California, Herring are found offshore during the spring and summer months foraging in the open ocean. The largest spawning aggregations in California occur in San Francisco and Tomales Bays. Beginning as early as October and continuing as late as April, schools of adult herring migrate inshore to bays and estuaries to spawn.” https://wildlife.ca.gov/Fishing/Commercial/Herring

Young Pacific Herring: from top to bottom – larval, early juvenile, older juvenile.

Adult Pacific Herring lay eggs on eelgrass beds in the northern portions of San Francisco Bay. Like English Sole, Herring fry drift all over the Bay soon after hatch. Herring are known to spawn as far south as Dumbarton Bridge but only rarely.

However, many of the young Herring caught on the March weekend were still in late-larval stage. Recall that in January, we caught three gravid-looking adults at different times in Coyote Creek. At least a few Herring may have spawned in, or near, the restored ponds this year!

There is some literature linking ocean cycles and Pacific Herring recruitment to in the Bering Sea (Zebdi and Collie 1995), but the connection appears to be complicated. This will require further investigation.

More Herring babies at Art2!

Young Staghorn Sculpin at Alv1.

Pacific Staghorn Sculpin babies were caught at ALL 20 STATIONS!

Staghorn Sculpins are a common fish caught at piers all along the west coast from Baja to British Colombia. I do not know why La Nina would cause Sculpin populations to surge here. Rain was scarce, so that was not a factor.

2. Bat Rays and big fish.

Tubful of Bat Rays at LSB2.

Eight Bat Rays were caught at LSB stations. We should see more of these as the season warms.

Holes in the lower channel banks between stations Alv1 and Alv2.

Lots of holes below the tideline along Alviso Slough. We spotted hundreds of holes just above the low tide line between stations Alv1 and Alv2. Micah suggested that Bat Rays are the most likely culprits. They dig for clams, worms, shrimp, and small fish. I can’t think of any other animal capable or inclined to dig so many holes.

I imagine that thousands of small Sculpin and English Sole could be making Bat Rays go crazy right now.

Nine Striped Bass were caught in March. Some of these were legal catch size. Without a doubt, the stripers are feeding on this baby fish bonanza. I have very mixed feelings about these non-native predators.

California Halibut and Plainfin Midshipman at LSB2.

California Halibut tend to proliferate in El Nino years. So, those we are seeing now are fewer but also a little larger and older. Only 14 were caught this month compared to 146 and 153 in March of 2015 & 2016 respectively.

Plainfin Midshipman. Until last month, we have never caught adult Plainfin Midshipmen. This month we caught three more full-sized adults. We have long suspected that adults must live near LSB stations because we catch several to a dozen young ones in most years.

Plainfin Midshipman – His underside is covered with rows of light-emitting photophores. This fish sings AND glows in the dark.

Sturgeon spotted on sonar at Coy1.

White Sturgeon. Two big fish were seen on the sonar screen as we trawled station Coy1.

3. Shrimp Wars.

Palaemon shrimp with eggs and some Black-tail Crangon at Alv3

Almost 2,600 Palaemon were caught this month and over 6,000 so far for 2021. For better and for worse, this is the best Palaemon winter we have seen so far.

Many Palaemon shrimp are brooded up and getting ready for egg release. Brooding season for native Crangon shrimp ends as weather warms and Palaemon brooding begins.

Just over 2,000 Crangon were netted. This rainless winter should hurt Crangon numbers, but surprisingly this is our best catch for a March since 2014. For some reason, Crangon are continuing to do well.

- Crangon nigricauda (black-tails) continue to predominate at LSB2 where salinity is highest.

- Crangon franciscorum (brown-tails) were congregating farther upstream on Coyote Creek and Alviso Slough. These were young shrimp, no more than a few to several months old. Young Crangon franciscorum generally seek fresher water.

4. Other baby fish.

Baby Anchovies and baby gobies from Pond A21.

Anchovy Babies! Anchovies continue to do well this year: 1,570 caught since January. The majority are very young fry from the spawn of 2020. Very young, nearly-transparent larvae, like the one at top above, probably hatched after the November cold snap. This suggests that a later spawn, possibly a winter-run, occurred in or after December.

Goby Babies! We counted over 1,800 “unidentified” baby gobies. These were too small to identify by species. Most were probably Yellowfin Gobies. This “Unidentified Goby” surge usually happens in April.

White Croakers & Bay Gobies are still showing up. Eight Croakers and four Bay Gobies were caught mainly at downstream stations. All were babies. We saw them in February and March of 2020 as well. Adult populations must be spawning close by in LSB or perhaps a little further to the north.

5. Polyorchis – The Red-eyed Medusa.

Polyorchis penicillatus at LSB2.

We caught another Polyorchis, or “Red-eye Medusa,” in LSB. You may recall we caught our first one in December. Again, each tiny magenta-red dot at the base of each tentacle is an eyespot.

This specimen has more gonad structure hanging down inside the inner bell. I am guessing that this one might be female, or simply more mature. This jelly feeds off the bottom during the day and swims up the water column at night. https://www.centralcoastbiodiversity.org/red-eye-medusa-bull-polyorchis-pencillatus.html

Red-eye Medusa studying our laminated Jellyfish guide.

Nearly all other jellies we ever catch are either ctenophores or unidentified “boogers.”

6. Longfin Smelt Spawning Grounds.

More spawning Longfins!!! It is getting late in the Longfin Spawning season, yet the spawn continues. Again, we caught milting males and at least one female spewing many eggs in, and near, the Coyote Creek “Spawning Grounds” we identified last month.

As far as spawning readiness goes, these fish are off the chart. We have never seen such darkly pigmented males or females so visibly plump with eggs.

Once again, we saw spatial segregation by sex. Longfins at downstream stations tended to be mostly females; those caught at upstream were majority male.

According to Longfin spawning theory, males prepare spawning sites in fresher water. Females feed and wait downstream as their bellies swell with eggs. When the females can no longer resist the urge, they swim upstream to find the males. The courtship dance and release of eggs and milt usually occurs after sunset, so we think. Some say that females spawn only once, but we suspect they spawn multiple years and maybe even multiple times per year. … Whatever way they do it, they are doing it here; in this exact spot!

7. Too many baby fish!

Western Grebes were on patrol at LSB2. When times are good, this place is a giant bird feeder.

Too many fish! Micah was exhausted.

Too many fish! Micah was exhausted.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post