Fish in the Bay – May 2021: Finishing off the La Nina spring.

Trawl map.

May Trawls. May is typically a low-fish transition month between “Baby Fish Month” of April and summertime Anchovies. However, May 2021 defied our expectations. Fish counts are still very high and there were a few other surprises.

After highlighting several species on the map I realized there is no theme for May. It was all a giant fish and bug kaleidoscope that seems to turn with tides and celestial cycles – as I will attempt to explain below.

Bay-side stations trawling results.

Most of the baby fish populations that boomed in March and April are now gone, so May is technically no longer a “baby fish month.” But, different critters are always spawning, or birthing, in Lower South Bay.

- Staghorn Sculpin numbers declined since April. Nonetheless, we counted a record catch for a May, and Staghorns were caught at every station. Staghorns are still on track to beat the previous record year of 2012.

- Yellowfin Gobies and “Unidentified Gobies” also persist. The May count of “Unidentified Gobies” simply adds to the already record-breaking year.

New Babies!

- Chameleon Gobies were spawning at LSB1.

- Leopard Sharks, Bat Rays, and Plainfin Midshipmen babies showed up at Lower Coyote Creek and LSB stations.

- Harbor Seal pups were spotted at Calaveras Point.

Upstream of Railroad Bridge.

Upstream stations are gradually salting up as we head into summer. This dry year is clobbering stands of California bulrush and other freshwater to brackish plants. However, against expectations, lots of baby native Crangon Shrimp were still counted which is very good news.

UC Davis research boat in Artesian Slough on Saturday morning.

1. Baby Fish Persist in a La Nina spring!

Yellowfin Gobies at Art2.

Yellowfin Gobies. For a second month, Yellowfin Goby numbers are way up again. 420 were mainly at upstream stations. 351 were collected in Artesian Slough alone.

Small “Unidentified Gobies” (which are also mainly baby Yellowfins) declined to 609 in May. But, this still adds up to over 4,400 baby “Unidentifieds” in 2021 with 7 months remaining! The previous record was 3,004 set in 2017.

Staghorn Sculpin. Staghorn Sculpin numbers came down a bit, dropping from over 2,400 in each of the previous two months to 1,680 in May. This is still a lot of Staghorns. The 2021 Staghorn count is currently 6,881. We will likely beat the old record of 8,400 set in 2012, our last strong La Nina year.

Young English Sole and other fishes at Alv3.

English Sole young rarely show up in the Bay outside the months of January through May. So, not surprisingly, numbers dropped from several hundred in April to 109 in May. We have already counted more English Sole in 2021 than in any of the previous ten years.

Herring Dorsal Colors change with salinity: Golden-brown, Green, and Blue.

Pacific Herring. Only four Herring were caught in May. Like English Sole, Baby Herring usually clear out of Lower South Bay after early spring. These are some of the last stragglers after the record Baby Herring explosion in March.

Herring Dorsal Color. As discussed in the January blog, dorsal colors in Pacific Herring, and some other Clupeiforms, change quickly in response to changes in salinity: 1) golden-brown in low salinity, 2) green in mid-salinity, 3) blue at high salinity. (See January blog, parts 5 and 6: http://www.ogfishlab.com/2021/01/09/fish-in-the-bay-january-2021-part-1-winter-fishes-longfin-shad-herring-anchovy/ )

Plainfin Midshipmen. In February and March, we caught full-sized adult Plainfin Midshipmen for the first time. Those adults must have been busy. In May, we found 21 baby Midshipmen at stations Alv3, Coy2, Coy4, and LSB1.

An adult male Midshipman can guard hundreds of eggs in a single nest, but the geographical spread of these babies suggest that multiple hatches occurred. It is likely that the recent La Nina phase of the ENSO cycle boosted recruitment of these fish as well.

First catch in Artesian Slough: 5 of the 11 Striped Bass plus an American Shad.

Striped Bass. Another 32 Stripers were caught in May; the same number as last month. These young Bass continue to feed on small fish and shrimp that hatched or migrated into LSB over the past spring.

In theory, we should see larger bass downstream in the deeper Bay. However, always keep in mind that larger bass hear us coming and can easily outswim our trawl nets.

Deep thoughts about La Nina fish explosions.

Fish and shrimp counts took a sharp upward turn starting in mid-2020: Anchovy, Inland Silverside, and Crangon Shrimp numbers surged over the months after May last year. At first, we thought it could have been a result of COVID-induced reduction of human activity. But explosions of Staghorn, Herring, and English Sole populations in early 2021 point to La Nina and the larger El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle.

Every few to several years Earth’s Tradewinds blow harder and push warm surface waters westward across the oceans. Sea surface temperatures on the east side of the Pacific drop by a few degrees, and cool nutrient-laden water upwells along the coasts of North and South America. Peruvian fishermen figured out that fish numbers peak during La Nina years some centuries ago, but we are still puzzling this out using a decade of monthly fish counts.

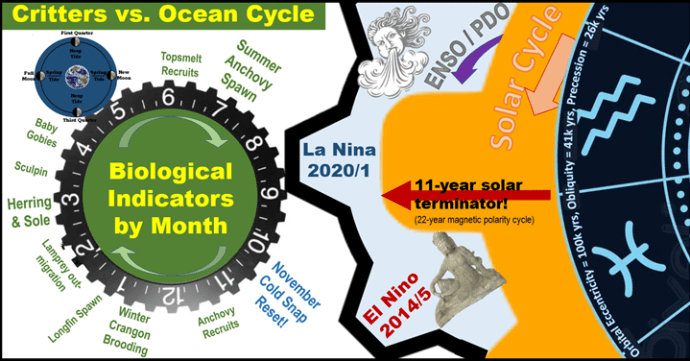

A new study that came out in April shows a strong correlation between the Sun’s 22-year magnetic polarity cycle and abrupt shifts from El Nino to La Nina conditions in the Pacific. The authors point to a magnetic “terminator” event that occurs every 11 years just after solar minimum at the end of each solar cycle when ENSO flips from El Nino to La Nina.

Active Sun = strong magnetic field = reduced cosmic rays bombarding Earth’s atmosphere – and vice versa. The resulting cosmic-ray flux affects the proportion of Carbon 14 isotopes in the atmosphere, among other things. Cosmic rays convert N14 to C14 a dozen kilometers up. The change in isotopes can be measured in tree tissue many centuries later. But, do cosmic rays and the Sun’s magnetic flux also affect the ENSO cycle? Correlation, yes! Causation, maybe.

- Press release describing the recent research: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2021/04/210405075853.htm

- The paper itself: Leamon, McIntosh, and Marsh (2021) “Termination of Solar Cycles and Correlated Tropospheric Variability.” Earth and Space Science. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2020EA001223

- WaPo article: https://www.washingtonpost.com/weather/2021/05/08/sun-el-nino-study/

- The 22-year “Hale Cycle,” aka “Hale Polarity Law,” was first deduced in the early 1900s. Later studies have determined that the Sun’s magnetic polarity has followed this cycle with regularity for at least centuries, if not millennia. https://www2.hao.ucar.edu/Education/Sun/hales-sunspot-polarity-law

- Owens et al. (2015) “The heliospheric Hale cycle over the last 300 years and its implications for a “lost” late 18th-century solar cycle” https://www.swsc-journal.org/articles/swsc/full_html/2015/01/swsc150038/swsc150038.html

The mind reels. Can cosmic rays indirectly induce a decadal trophic cascade in SF Bay? Based on a very rough correlation in 10 years of fish and bug data, I felt inspired to make a conceptual diagram depicting the Sun, Earth, and Bay fish and bugs as cogs in a giant celestial machine. It made sense for a while. Then I realized that I got one of my wheels backward in the diagram. Now, I must move on.

2. Bay Pipefish

Two Bay Pipefish at Coy1

Bay Pipefish. This was a good month for Pipefish: we netted nine. These small sea horses hide in tules close to the shoreline, so they get scooped up in our net largely by accident. We have seen more in certain months, but we usually see fewer.

Baby Bay Pipefish swimming amongst a sea of Ctenophores in Pond A21.

With their tiny mouths, I always interpret presence of Pipefish as solid confirmation that tiny food, like rotifers and copepod nauplii, must be sustaining them.

3. Shrimp Wars

Exopalaemon Shrimp at Art2.

Exopalaemon Shrimp. 347 ‘Exos’ were netted this May. These are the non-native freshwater shrimp from Asia that arrived in the Bay Area in the early 2000s. All were caught at upstream stations, none downstream of the railroad bridge. As seen in the photo, most appeared to be egg-bearing females. High salinity is keeping these invaders bottled up at upstream stations.

Palaemon Shrimp at Art3. Nearly all of these were berried females.

Palaemon Shrimp. Unfortunately, 2021 is a very good year for non-native Palaemon shrimp: almost 3,800 were counted in May. The total count for the year already exceeds all but two of the last 10 years. Continued high salinity practically assures that this year will be a record-breaker.

Most Palaemon Shrimp at upstream stations were egg-bearing females. Further downstream, there were more small and non-egg bearing Palaemon amongst the pregnant females. Adult female Palaemon probably migrate upstream to release broods during the warm season just as adult female Crangon do in winter.

Crangon Shrimp at Art3; some of these were super tiny – finger is shown for scale.

Crangon franciscorum (brown-tails). Good News: 2021 continues to be very good for native Crangon shrimp: more than 6,000 were counted in May and almost 16,000 year-to-date. All these Crangon were small, young, and presumably male. Hopefully, this promising trend will continue through the year.

4. Chameleon Gobies spawn at LSB1

The Chameleon Goby scene at LSB1.

Chameleon Gobies change color from light tan with dark stripes to dark brown/almost black. Color changing is how they got named “chameleon.” Young Chameleon Gobies invariably display the light-tan-with-stripes look. Even adult females generally show the lighter color. Males get really dark, especially during spawning season.

A few of the striped females looked very chubby on the May weekend, so I performed a gentle egg-check on one of them. She was full of eggs! We can now add a new fish and new location to our inventory of spawning fishes in Lower South Bay!

5. Jellies and Ctenophores.

Pacific Sea Nettles. We caught seven Pacific Sea Nettles in May, in addition to two in April. We don’t usually see these.

Ctenophores, aka “Comb Jellies”. A very rare late spring Ctenophore bloom in April continued thru May. Over 3,600 were counted in April and then more than 5,000 in May! Our trawls sweep through just a small portion of Lower South Bay. Imagine how many millions of these crystal pearls must be swimming around in the Bay!

We only been tracking Comb Jellies for a few years, but this is the first time we observed a significant bloom outside of the coldest months of December thru March. This late-season bloom could be caused by either cool sea surface temperatures, enhanced zooplankton production, elevated salinity from reduced rain fall, or a combination of all three.

6. Two Flatfishes.

All eight Starry Flounder caught in May were small: one to two inches standard length.

Starry Flounder. We were surprised this month to find eight baby Starry Flounder. Starries swim upstream into the mouths of rivers and creeks to lay eggs.

The small sizes of these individuals (postage-stamp size!) indicate that Starries are hatching either in, or immediately upstream of our Anchovy/Longfin/Sculpin Spawning Grounds near UCoy1/Dmp1!

Diamond Turbot at LSB2

Diamond Turbot. This might be the largest Turbot we have ever caught. Along the coast, they often grow to 18 inches. They are a popular righteye flounder game fish on the coast. https://www.pierfishing.com/diamond-turbot/

7. Leopard Sharks and Bat Rays

Micah showing off an adult Leopard Shark at LSB1

Leopard Sharks. We caught 11 Leopard Sharks in May. (This was our second highest Leopard Shark catch after April 2015.)

This is shark-pupping season. Female Leopard Sharks migrate into South and Lower South San Francisco Bay to give live birth to pups. 9 of the 11 sharks caught on Sunday were teeny-tiny babies only several inches long. These newborns were only days old!

More baby sharks at Coy4. Have you ever seen such tiny baby sharks???

Copepod parasites afflict our Leopard Sharks! A 2013 paper by Ronald Russo lists five common parasites on Leopard Sharks: 1. Achtheinus oblongus, 2. Branchellion lobata, 3. Pandarus bicolor, 4. Echthrogaleus coleoptratus, and 5. Lernaeopoda galei. (B. lobata is a marine leech. P. bicolor is bicolored. The latter two are internal types of parasites found on gill arches and in buccal and nare cavities.) https://nrm.dfg.ca.gov/FileHandler.ashx?DocumentID=78260&inline=1 By process of elimination, this parasitic copepod is A. oblongus!

- In October 2020, We also found A. oblongus on our Brown Smoothhound sharks.

- This is still the best shark parasite library I have found on the internet: https://www.shark-references.com/literature/listBySpecies/Achtheinus-oblongus

Micah with 2 of the 20 Bat Rays caught on Sunday.

Bat Rays show up as the waters warm. We netted 20 in May. Our record still stand at 43 in October 2015, an El Nino year. But, twenty Rays is the new 10-year record for a May. We should see more of them as this season warms.

8. Harbor Seals.

Harbor Seals. A colony of Harbor Seals lounges on the mudbanks at Calaveras Point during low tides. They forage for fish when the water rises. Because of iron, or something, the coats of Seals in this bay turn red as they age. … These are some of “The Red Seals of San Francisco Bay.”

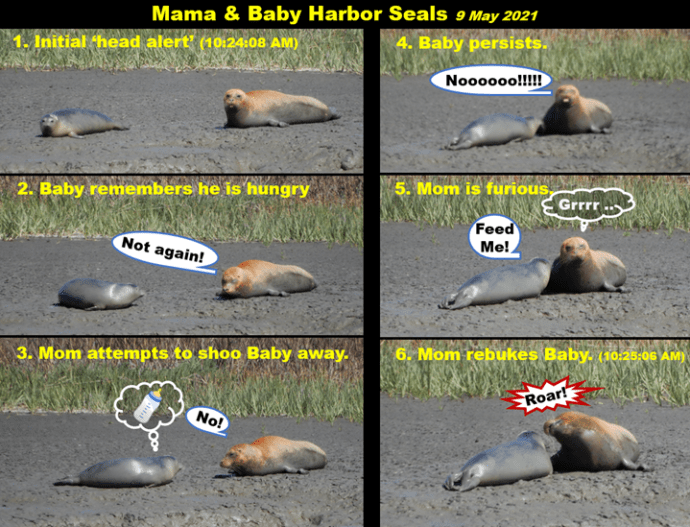

March through July is Harbor Seal pupping season. In this sequence, Mama seal is in the process of weaning her baby.

- Baby was peacefully daydreaming until we showed up.

- Baby was curious. He watched us for a full 20 seconds.

- Then after that initial ‘head alert’, Baby forgot about us and remembered he was hungry. He waddled back to Mom expecting to be fed.

- Mom was not happy and ultimately gave Baby a firm ‘NO!’ at the 58-second mark.

Conclusion: A portion of Mom’s peaceful Sunday morning was ruined because we disturbed Baby.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post