Fish in the Bay – June 2021: Summer Fishes.

Trawl map.

June Trawls. The summertime Anchovy spawn commenced in June: see previous Anchovy Alert blog post – http://www.ogfishlab.com/2021/06/05/fish-in-the-bay-june-2021-anchovy-alert-spawning-anchovies-have-returned-to-lower-south-san-francisco-bay/. This post summarizes everything, other than Anchovies.

Bay-side stations trawling results.

Summer temperatures warm marsh waters. At the same time, algal growth (mainly phytoplankton) causes Dissolved Oxygen concentrations to rise and then fall to near zero on a daily basis.

Fewer specialized fishes tolerate this warm-season swamp environment. Overall fish counts usually drop as Shad, Herring, Longfin Smelt, and English Sole flee the area. Only the arriving Anchovies substantially offset this seasonal fish decline.

Upstream of Railroad Bridge.

Lowest DO ever! Dissolved Oxygen was low across the board at upstream stations on Saturday morning.

DO readings at station UCoy1 were the lowest of all: Top and bottom DO ranged from 2.6 mg/l to 1.5 at the beginning and end of the trawl. The only fishes that endured this naturally anoxic quagmire were: Northern Anchovy, Rainwater Killifish, and a Longjaw Mudsucker!

1. A few Low DO Specialists.

Longjaw Mudsucker. Ten Mudsuckers were netted in June; the highest count since June of last year. These native gobies are adapted to survive when dissolved oxygen (DO) drops to near zero. They survive for many hours when stranded out of water by breathing air through buccal cavities and even their smooth skin! Mudsuckers might be ecologically analogous to frogs in this brackish marsh.

Rainwater Killifish. We only caught a few dozen killifish in June. These tiny fish hide in vegetation along the shorelines where trawl nets cannot catch them. No doubt many more were missed.

- Rainwater Killifish are ultimate survivors that tolerate salinity from zero to 80 ppt and DO as low as 2 mg/l. http://calfish.ucdavis.edu/species/?ds=698&uid=119

Young Yellowfin Goby with two smaller Yellowfins (chubby bodies) and two Cheekspots (long snake-like bodies), Pond A18, 5 June 2021.

Other Gobies. Gobies generally tolerate low DO better than most other fishes. Non-native Yellowfins and native Cheekspot Gobies and Arrow Gobies are amongst our most prolific species when waters get stagnant.

2. Other Summer Fishes.

Starry Flounder. Eight tiny baby Starries were caught in both May and June. Starries must have recently spawned near the creek mouths.

Starry abundance fluctuates year by year: From early 2019 until May 2021, we caught only one or two Starries each month. In contrast, we caught dozens per month in 2017 through 2018, usually none in 2016, a dozen per month in 2015, then again practically none in 2014. I cannot explain this up and down Starry abundance pattern.

Striped Bass at UCoy2. This Bass is showing possible Lamprey wounds.

Striped Bass. The 2021 Bass count already exceeds the year-end tallies for 2018. 2019, and 2020. Both warm temperature and low DO will eventually inhibit bass as summer progresses.

Lamprey Bites? The Bass shown above has wounds that could be Lamprey bites. Young Lampreys (macrophthalmia stage) at around 5 years of age migrate out to sea from the local freshwater creeks. Lampreys begin feeding on bigger fish at that age.

- Marine Lampreys feed on Striped Bass on the East Coast: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Oiq9taSu5hU

3. Some Fish from the Deep Bay.

Pacific Herring. Three young straggling Herring were caught at LSB stations. These are probably among the last of the spring 2021 spawn that has now migrated out to the ocean.

Baby Plainfin Midshipmen, Alv3, 6 June 2021.

Plainfin Midshipman. Three more baby Midshipmen were caught at Alv3 in June. This native bottom-dwelling fish is found in most of the deeper parts of SF Bay. As long as salinity remains fairly high, Midshipmen should continue pushing upstream into Lower South Bay.

California Halibut. Six more young Halibut were picked up in June. The pair shown above was interesting because before and after photos show how quickly Halibut can lighten or darken their shade of brown.

4. The Emperor’s Gobies.

Shimofuri Goby. This was the only Shimofuri caught in June. Shimofuri and Chameleon Gobies are similar-looking close cousins. Salinity usually segregates the two: Shimofuris prefer brackish sloughs and creeks. They cannot tolerate marine salinity.

The Shimo shown above is an attractive alpha male:

- Dorsal and anal fins are dark gray with an orange margin.

- His cheeks are peppered with tiny light-colored spots that extend under the jaw. In Chameleon Gobies, those face spots are always fewer, larger, and never present under the jaw.

- When ready to attract females and guard his mating cave, his brown body will darken considerably.

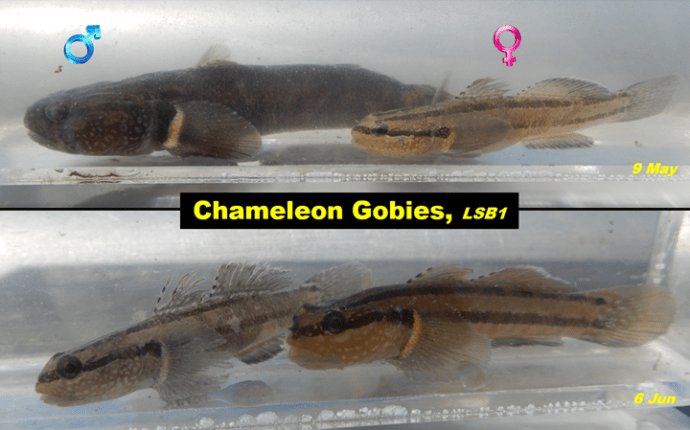

Chameleon Gobies. Chameleon Gobies were caught at our Chameleon Goby hot-spot at LSB1 in both May and June. Two different photos from both months are combined above to show the different appearances of Chameleons.

Shimofuris and Chameleons are also color-changing fish! The young of both species are light-brown with dark stripes. Adults, possibly only males, can darken to almost black, and they change color from light to dark and vice versa within a few minutes.

Anal fin and spots under the chin are key. The Chameleon Goby anal fin has a red stripe near the base followed by light and dark stripes and a white margin. But, the anal fin and face spots are hard to see on a tiny wriggling fish. We usually guesstimate that those caught in high salinity are Chameleon and the others caught in brackish water are Shimofuris, but that is not always correct.

Japanese Emperor Akihito was the first to distinguish Shimofuri from Chameleon Gobies (https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?speciesID=716). He has described at least 10 species of gobies over several decades and is still researching at age 87!

- Article in Japan times: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2021/06/24/national/emperor-emeritus-akihito-discovers-two-goby-fish-species/

- Akihito and Ikeda (2021) “Descriptions of two new species of Callogobius (Gobiidae) found in Japan.” https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10228-021-00817-2

- Article about Akihito from 2019: https://www.shine.cn/news/metro/1905054106/

- This tropical goby is named for Akihito: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exyrias_akihito

5. Sharks and Rays.

Leopard Sharks. All 10 Leopard Sharks caught in the downstream side on Sunday were small babies. We caught almost the same number of babies the previous month. The 2021 shark pupping season seems to be going well.

Micah with two baby boy Leopard Sharks at Alv3.

Leopard Shark Photo Op #1. Many will disagree, but for objectively evaluating the health of Lower South San Francisco Bay, monthly shark counts are not crucially important beyond presence (good) or absence (bad) in the warm season. But, we are always in awe of such exotic fish.

Four sharks subdued (and released) with a single mighty hand!

Leopard Shark Photo Op #2. Leopard Sharks compete with Bald Eagles as the #1 charismatic megafauna in LSB – at least in my opinion.

Copepod Parasite. One of two baby Leopard Sharks at Coy4 hosted a new parasitic copepod glued to the top of her head. This is NOT Achtheinus Oblongus which we have previously found parasitizing both Leopard Sharks and Brown Smoothhounds.

What species is this copepod? Someone, somewhere has identified this bug. This one is greenish and shorter-bodied than A. Oblongus. It (he) lacks the twin ‘tails’ of egg strings, so I presume this parasite may be a male.

Two baby girl Leopard Sharks (minus copepod parasite) on a bed of Crangon Shrimp at Coy4. What do you suppose the sharks eat?

A baby girl Bat Ray (no claspers) at Coy4.

Bat Rays. All but one of the 8 Bat Rays were ‘babies’ (~200 to 300 mm wingspan). Even the largest one was less than 500 mm (20 inches) across.

6. Harbor Seals.

A young Harbor Seal swam with us for a short distance at Alv3.

Harbor Seals. We do not perform seal counts at Calaveras Pont each month, so I cannot say if the colony is growing. The seals were particularly conspicuous as we passed by stations Alv3 and Coy4.

Seal lounging in sprouting Spartina near Coy4.

Calaveras Point is a seal rookery. Many new pups arrived this spring. We observed mama seals weaning pups in May. The coats of SF Bay Harbor Seals turn redder as they age. With practice, we could probably guess the age of each seal by the redness of his or her coat.

If you visit:

- Always observe from a distance. The south-facing beach of Calaveras Point is both a year-round seal haul out and rookery from around February thru June.

- Never yell or wave at the seals. They see you, and they will look at you. But, they are much more interesting to watch after they forget about you and resume their normal seal business.

7. Crustacean Corner

Mud Crabs (aka “shore crabs”). We encountered 5 Oregon and 6 Harris Mud Crabs in June. (Two of the Harris crabs had egg broods and the Oregon crabs were newly hatched.) These two shore crabs used to be much more common. As mentioned in previous blog posts, the non-native Harris Mud Crab was the most common invertebrate caught in Lower South Bay in trawls from 1981 through 1986.

Marine Crabs. NONE! You may recall that we were seeing an unusual number of young Decorator and Dungeness Crabs this time last year. These marine crabs were last seen in October. Bay salinity is more than high enough to support them, but they have not returned yet.

Why do we see so few crabs? This is probably because crabs are delicious. Everything bigger than a crab, eats the crab. Thus, low crab counts in Lower South Bay may be inversely proportional to the numbers of Seals, Leopard Sharks, Bat Rays, Sturgeon, Heron, Egrets, etc.

Ghost Shrimp look like miniature lobsters and taste just as good. Many experts have told me that Sturgeon go crazy over Ghost Shrimp.

- This was only the second Ghost Shrimp we have ever caught. They burrow 18 inches deep in mud and sand on shallow banks where our trawling net cannot reach them. https://thelostanchovy.com/kayak-fishing-tutorials/ghost-shrimp-pumping-tutorial/

- It is possible that this one was someone’s bait that escaped. https://www.pierfishing.com/msgboard/index.php?threads/bait-%E2%80%94-ghost-shrimp.1278/#post-6136

Exopalaemon shrimp at Dmp1.

Exopalaemon shrimp. Exopalaemon numbers have been dropping since March as should be expected in a high salinity year.

Palaemon shrimp at Alv2.

Palaemon shrimp are doing well. The annual count now exceeds 15,000 as of June. If the trend continues, 2021 may end up being the best Palaemon year on record.

Young Crangon shrimp with several larger red Palaemon females mixed in at Coy4.

Crangon Shrimp. Crangon continue to do well this year: almost 18,000 year-to-date. But, the count was much higher by this time last year. High salinity may inhibit their continued recruitment this summer.

8. Dry, Salty Marshes.

Rainless winter hammered Calfornia bulrush and Alkali bulrush all around our upstream stations. Peppergrass has assumed dominance on the high ground. Spartina is filling in along the waterline.

Peppergrass. In the absence of winter rain, non-native peppergrass has taken over the landscape around Dump Slough and Upper Coyote Creek. Most of the area is covered in a tall carpet of white flowering heads of Peppergrass, aka Pepperweed.

Bad News: This variety is Lepidium latifolium. It is a number-one invasive plant in marshes in this part of California. https://www.cal-ipc.org/plants/profile/lepidium-latifolium-profile/

Good News (sort of): Peppergrass is part of the mustard/cabbage family. Most, if not all varieties are highly edible and have been cultivated around the world since the ancient Romans and Incas.

- latifolium: “In Ladakh in the Himalayas, the spring leaves are prized as a vegetable. The peppery edge or bitterness is removed by first boiling the young shoots and leaves, and then soaking in water for two days. Cooked like spinach, it makes a nutritious vegetable.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lepidium_latifolium

- For science, Micah and I chewed on a few Peppergrass leaves from Alviso Slough on the July weekend. The flavor is slightly reminiscent of Arugula. If safe, it could be potential salad material. More tests are needed!

- The L. Virginicum variety of Peppergrass is more commonly harvested for salads in the US. https://www.ediblewildfood.com/peppergrass.aspx

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post