Fish in the Bay – March 2023, Freshwater Flushing & Spawning Fishes!

Atmospheric rivers and rainwater flushing continued through March. This extended rainy season is a very welcome change after at least three years of La Nina drought. https://www.drought.gov/drought-status-updates/drought-status-update-and-2020-recap-california-nevada

For the short term, fish counts continued to be a bit low due to low salinity. This lower portion of San Francisco Bay was once again a proper river mouth! Marine fishes we are accustomed to seeing, like Northern Anchovies and English Sole, and even adult Crangon were again pushed into deeper saltier water farther out in the Bay.

Good news! Despite low numbers, Longfin Smelt, Staghorn Sculpin, and Yellowfin Gobies showed continued signs of spawning readiness and/or recruitment.

1. Storm Gods & Dead Shells.

A looming Storm God descends on the valley

Micah pointed out a particularly tall thundercloud to the south of us as we motored down Alviso Slough on Sunday. He said it looked like the classic anvil-shape of a thunderhead that portends a big storm. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cumulonimbus_incus

To me, it looked like an angry storm god with arms outstretched and head tilted down regarding the mortals below. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Weather_god

- Micah felt glad everyone had extra rain gear.

- I felt glad we sacrificed a donut to the water gods as we started our trip a that morning.

Throughout both 4 and 5 March, tall thunder clouds and line squalls (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Squall_line) drifted in from the ocean. This was starkly different from the calm flat “La Nina sky” we experienced over the past three springs. The warmer ocean creates tall moisture-laden clouds!

- The Pacific Ocean flipped from La Nina to neutral by March. Will El Nino be coming next? https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/march-2023-enso-update-no-more-la-ni%C3%B1a

Recently dead and dying Musculista shells at Alv2.

We also continued to find dead or dying Musculista shells, and even some dying Eastern Mud Snails, at upstream station. These hardy mollusks can take quite a beating, but multiple months of freshwater flush is too much for many of them.

2. Late Winter Spawning Fishes.

Longfin Smelt. 219 Longfins were caught. This was our second-highest total for a March after last year’s haul of 540. Presumably/hopefully, this season’s number was a bit suppressed due to the massive rainwater flushing we were experiencing.

Longfin sexual segregation also continued to be readily apparent. Females and young made up the vast majority of all Longfins caught at downstream stations. Their full bellies indicated they were feeding and/or swelling with eggs.

Darker males, with extended anal fins and protruding belly flaps, continued to congregate in the fresher waters near station UCoy1.

Make no mistake, abundant rain and freshwater flushing encourage Longfin Smelt to spawn. The fry that hatch into these fresh and cool conditions should have a much higher chance of survival.

Yellowfin Goby. 15 adults were netted. All but a few of those were clearly gravid females with bulging bellies. February thru March is Yellowfin spawning time.

Males can be very conspicuous. Their heads take on a broad shovel-like shape and appear reddish and swollen. This may be a result of their burrowing activity as they build a y-shaped love tunnel in the muddy bottom. Each male will strive to entice at least one female to deposit eggs in his burrow. He will then fertilize and guard the eggs until hatch roughly 30 days later.

“Baby Fish Month” is coming! We typically count hundreds to thousands of tiny Yellowfin fry in April.

Young Staghorns at Art3 on March 4th.

Staghorn Sculpin. The Staghorn count for March was 161. This was a substantial increase over January (one staghorn caught) and February (30). All but a few of those we saw in March were newly hatched or juvenile.

Climate affects Staghorns and English Sole somewhat similarly. La Nina and cool ocean upwelling along the coast boosts the overall populations of both species. Adults of both species live along the coast, or at least closer to the coast.

- English Sole spawn in the ocean with larvae and juveniles migrating toward the mouths of estuarine creeks for recruitment during the rainy season.

- In contrast, Staghorn adults migrate upstream seeking low-salinity marshes as their spawning locations.

Baby Staghorns roughly 10 mm long. Many mysids are shown for scale.

Staghorns spawn during the coldest months – around December through March. Some caught in March had hatched only days earlier! Most of the tiny baby Staghorn fry were caught in restored Pond A19. Once again, this is a Staghorn spawning place!

3. More Silvery Fishes

American Shad (Alosa sapidissima). 17 were caught. That is a fairly typical number for a March. The shad shown above is still young, but it was among the largest we ever see. Larger, sexually mature Shad spawn in the big Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers. The big ones probably spend more time at sea as well.

- Katarina Tosic, a fish researcher in Romania, studies Pontic Shad (Alosa immaculata) from the Black Sea and Danube river region. She told me that the Shad there appear to have darker or lighter (transparent) heads depending on location of catch. She jokingly refers to them as blonde or brunette Shad.

- Katerina’s published paper is here: Tosic and Taflan (2019) Observations on Morphological Color Changes in Pontic Shad (Alosa Immaculata, Bennet 1835) during Spawning Migration in the Danube. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333675788_Observations_on_Morphological_Color_Changes_in_Pontic_Shad_Alosa_Immaculata_Bennet_1835_during_Spawning_Migration_in_the_Danube

“Abstract. The Pontic shad (Alosa immaculata, Bennett 1835) is a Black Sea member of the Clupeidae family that migrates into the Danube via the principal Danube Delta branches and spawns in the upstream reaches of the river. Spawning migration starts as early as February and can last well into the summer, with most commercial capture occurring during peak migration in April-May. The coloration of the fish varies in both color and shade, with clearly distinguishable dark-headed and light-headed individuals depending on the fishing location. Here we draw parallels between shad head coloration and turbidity of the Danube, its delta and Black Sea waters. … Ultimately, head coloration might be a useful indicator of where an individual was captured.”

Perhaps our SF Bay Shad also turn brunette-headed after spending some time at sea! Or, maybe brunette-headedness is a characteristic of advanced age or sexual maturity in Shad, Investigation continues!

Threadfin Shad (top) and four young Anchovies at LSB2 on 5 March.

Threadfin Shad. Only 9 Threadfins were seen. But again, that is fairly typical for a March in LSB.

Northern Anchovies. All of the 100 Anchovies were very young; post-larval to juvenile. All were caught at downstream stations where salinity was higher. Once again, these young recruits suggest that the summer-thru-fall 2022 spawning season was a productive success.

Many young Anchovies in the tub at LSB1 on 5 March 2023.

Striped Bass (top right), Threadfin Shad, and some young Crangon shrimp at Art2 on 4 March.

4. Brownish Bottom Fishes

English Sole & a Tomcod (left) at LSB2

English Sole. 59 English Sole were counted. Most of these were at the deeper, higher salinity LSB stations.

Published literature documents that English Sole is a “La Nina fish” on the Pacific Coast. Populations rise and fall in accordance with cool ocean upwelling and increased productivity in coastal waters. These young ones are further stimulated to migrate upstream by atmospheric rivers and freshwater flushing. Nonetheless, our decade of numbers indicate that La Nina and ocean upwelling is the more important factor affecting English Sole numbers here.

Pacific Tomcod. Seven more Tomcod were caught in March.

Goby and Sculpin side-by-side comparison.

Bay Goby. Another two very young Bay Gobies were counted in March. We have seen a few to a few dozen of these native gobies each spring since 2020. However, these fry do not appear to stick around LSB. The deeper Bay, just to the north of us, must be more hospitable for them these days.

5. Plainfin Midshipman – The Special Fish of the Month

Plainfin Midshipman, LSB1, 5 March 2023.

Plainfin Midshipman. We once again caught an adult Plainfin Midshipman on March 5th. We have been picking up one to a few adults for the past few years. Like the baby Bay Gobies, we tend to see Midshipmen in spring.

Same Midshipman showing singing mouth (top) and photophores on belly (bottom).

Midshipmen are very important forage fishes for larger fish and bird predators. When you pick one up, you understand why. They are very soft-bodied and fleshy. They have no spiky rays or staggy horns. They feel entirely like a smooth piece of meat. If I were a creature that could only eat fish live and raw, this one would be an attractive choice.

Same midshipman, profile view.

More importantly, this is the magical “Singing Toadfish.” … to repeat once again:

- Midshipmen males (type 1) can hum continuously for up to 2 hours. It is the longest vocalization by any animal on the planet.

- They glow in the dark. This one’s body is dotted with light-emitting photophores.

- They come in three sexes: Male type 1 (big macho males), male type 2 (small males that mimic females), and female. And,

- Midshipmen are purple. (Some may call it a purple shade of brown.)

6. Bad Bug.

Devil Bugs. We see many cymothoid isopod gill parasites (aka Devil Bugs) during the winter fish migration season. The extent to which the bugs are being carried in from the ocean or simply reside in the Bay waiting for suitable hosts is unknown.

One thing we see clearly: Devil Bugs appear to abandon their host when the host fish is jostled or struggling. More often than not, we spot Devil Bugs as they attempt to flee as we examine a fish. Also, more often than not, Devil Bugs immediately seek a new host to grapple onto.

This may make sense. Under natural conditions, e.g. when their host is being eaten, Devil Bugs must immediately ‘abandon ship’ so to speak.

- They are fast and agile swimmers.

- They appear to have no problem catching a new host. Each of their many legs has a needle-sharp tip for clinging.

- They are much smarter than they look.

(Full confession: I have no use for these parasites. I try to crush them whenever I find them.)

7. Good Bugs.

The bug community at LSB1.

Synidotea laticauda, the Isopod in the upper right corner, is interesting. It is the most common invertebrate we find in LSB. (It is non-native but well-established, so I included it as a “good” bug here.)

This organism was only observed in San Francisco Bay and Willapa Bay, Washington for over a century. No one knew there it came from, Then in 2017, molecular studies confirmed its likely native range near the Yangtze estuary in China. https://invasions.si.edu/nemesis/species_summary/546963

Crangon Shrimp. 461 Crangon is not bad for a March. The number is usually low this time of year. The adults can’t tolerate salinity much below 20 ppt, so they must remain far downstream while rivers are flushing and the creek mouths remain fresh.

The vast majority of Crangon were once again tiny recruits caught at upstream stations.

Young Crangon (top left) and several smaller Mysids (generally at lower right) caught at Coy1.

Mysids. These tiny, clear-bodied crustaceans are found in oceans, estuaries, and rivers throughout the world. We tend to think of them as “midget shrimp,” or perhaps “miniature krill.” In truth, they are neither shrimp nor krill even though they look and function a little similar to both. Mysids belong to their own crustacean order called Mysida. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mysida

Mysids bloom here in winter through spring when we experience good rainwater flushing. We are catching a lot more mysids this season than we have seen over the past three drought years. This is very beneficial for the ecosystem.

At least four different Mysid species are found in SF Bay. Neomysis kadiakensis tends to be the most common one we catch in low-salinity marshes, so I am guessing that is the identity of those shown in the photo above.

- This article from Maryland describes how Mysids are very important for the ecosystem, but hard to study. https://www.mdsg.umd.edu/onthebay-blog/mysterious-mysids-maryland-sea-grant-funded-scientists-are-using-innovative-methods

- Mysids are the BEST food for small fishes and other creatures. https://mysids.com/

- Live Mysids are EXPENSIVE food! (20 cents each, if you buy in quantity) https://www.aquaculturenurseryfarms.com/live-saltwater-fish-food/mysid-shrimp/

Roughly $80 worth of Mysids from Pond A19! $$$

8. Water Colors.

We tend to ignore the colors of San Francisco Bay water … until disaster strikes. Within the normal range of muddy brown to brownish green, the changes are subtle from upstream to downstream and from one month to the next. But, as we learned again last year, every decade or two a dark fish-killing red-brown stain can rapidly spread across the Bay.

Good News! Freshwater flushing this season should greatly reduce the likelihood of another red tide for the time being.

- River flushing and fresh sediment supply help feed the spring diatom bloom.

- Diatoms and other phytos feed everything else.

- As the year progresses, the tiniest fishes and bugs feed on nutritious unarmored flagellated phytoplankton cells that can cause red tides.

Literature supporting that last point is sparce. But, people who culture larval fish are aware. For example: “Although not commonly used as live feed for fish larvae, the heterotrophic dinoflagellate Oxyrrhis marina can be a potential candidate during the first feeding stages.” https://www.globalseafood.org/advocate/live-diets-for-larval-fish-shrimp-production-enrichment-feeding-strategies/

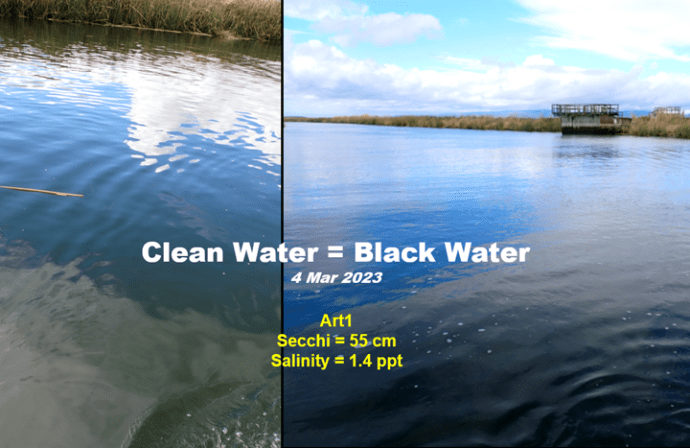

Fun Fact! Clean water, devoid of sediment and phytoplankton, looks black. Ian Wren and Jon Rosenfield from SF BayKeeper taught me this (https://baykeeper.org/content/our-team). They were both on the scene near Oakland and Alameda last August as the red tide struck. When the red tide died away on September 1st, they both documented that the water in the Oakland-Alameda Channel and at Seaplane Lagoon changed abruptly from red-brown to black!

Light penetrates deeply into clean water. The lack of light scatter from particulate matter makes water look black. Even small concentrations of minute sediment or phytoplankton particles make a stark difference that is readily seen by unaided eye.

Know your water! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gV7a22pVrj0

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post