Fish in the Bay – July 2023, Record Starry Year

Record Starry Year! As reported earlier, the year-to-date Starry count had already exceeded the previous record year as of June, (Previous record: 465 in 2012) We caught another 266 baby Starries in July which brought the 2023 total to 796!

Still very fresh. Salinity continued to be in the low single digits at almost all upstream stations. The freshness was impeding the arrival of summer-spawning Anchovies.

Salinities were higher at downstream stations but still fresh enough to discourage all but a few sharks and rays.

1. Starry Flounder Explosion Continues.

Baby Starry and Harris Mud Crab at Art2 on 1 July 2023.

Kathy Hieb at CDFW emailed to tell us that they are also counting high numbers of young Starry Flounder in the northern reach of the estuary, Suisun Bay and parts upstream. According to Kathy these are likely the highest numbers they have seen since the 1990s.

This might be what a typical Starry year looked like decades ago. Also according to Kathy, Starry Flounder were declining in the estuary before the CDFW Bay Study started in 1980. In the early 1980s, the Bay Study still collected adult Starry Flounder in the Bay, “but those days are long gone.”

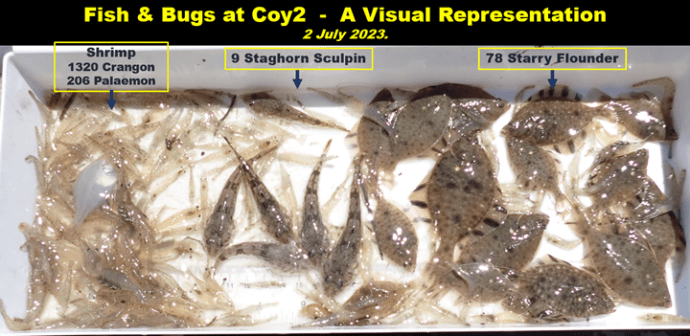

More baby Starries at Coy2 on 2 July 2023.

We must bring those days back! How can we do it?

2. July Trawling Weekend- Lots of Little Brown Fishes

Morning donut sacrifices. As mentioned many times in the past, we offer a tasty treat to the marsh sprits in hopes of a safe day on the water at the start of each trawling day.

Needless to say, there is both a right and a wrong way to do this. We experienced one of each in July:

- 1 July – the right way: Micah properly sacrificed a red-white-and-blue sprinkle donut in small pieces that quickly dissolved, disintegrated, and became one with the marsh.

- 2 July – the wrong way: California Gulls grabbed our donut.

With the exception of humans and gulls, nature generally abhors a donut. Refined corn syrup and processed starches provide quick energy in a pinch, but they are rarely healthy in the long-haul. Never feed a donut to wildlife you care about!

In the “wrong example” above, a flock of non-native California Gull mauraders suddenly swooped down and attacked our sacrifice before we could react. These are tough birds that regularly feed on garbage at the local landfills. When they aren’t eating garbage, they predate eggs and chicks of local native species. Nonetheless, we normally take steps to prevent these unhealthy Gull-donut interactions.

In contrast, microbial life in marsh water is perfectly adapted to break down sugars and complex carbs and quickly reintegrate them into cellular biomass. Thus, a potentially toxic brew of empty calories is converted into healthy short-chain fatty acids and proteins. Food for bacteria quickly becomes food for bigger organisms and eventually food for fishes. The donut sacrifice is our reminder of this proper cycle!

- A brief description of the correct way nature breaks things down. https://www.youtube.com/shorts/WUYLau_eqfc

- Why sacrifice a donut at all? In the words of Tevye from “Fiddler on the Roof” – TRADITION! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kDtabTufxao

Little brown fishes. Numbers of Gobies and Sculpins are rising as summer progresses. Some of these were tiny baby fishes that were too small to identify just a few months ago. Once they grow big enough, around 40 mm long in most cases, they become easily identifiable.

Shimofuri Goby count = 141. Young Shimos and Chameleon Gobies are easily distinguished from other baby Gobies by their longitudinal dark stripes. This is the Shimo/Chameleon body color we call “watermelon pattern.” Adults often display the darker “snakeskin” look, but they change back and forth depending on mood.

Kenji Soto, at CDFW, emailed last month to ask if the Shimofuri Goby ‘blue flash’ could be used as a field identification key. In my opinion, NO! The ‘blue flash’ is very attractive, and every adult Shimo appears to have one behind each operculum. But, the flash is very hard to detect except by macro photography.

Visual representation of shrimp and fish at Coy2

Detail of Staghorn Sculpins at Coy2

Staghorn Sculpin count – 163. That’s a lot of Staghorns for a July. Numbers usually taper off sharply by mid-summer. 2023 will not be close to a record Staghorn year, but the numbers are still pretty good.

3. Bigger Bay Fishes

California Halibut count = 6. It was good to see a few Halibut, but overall 2023 has been a little too cool, too fresh, and too much La Nina off the coast to make Halibut comfortable. The year-to-date count is 18 which is about as low as it has ever been. We will not see high Halibut numbers again unless or until strong El Nino conditions appear off the coast.

Leopard Shark count = 4. It is still a little too fresh for Leopard Sharks as well. At least one or two pregnant mamas delivered broods here so far, but 2023 will be a low Leopard Shark year.

Bat Ray count = 3. Three years of drought spoiled us: 2022 was our record shark and ray year. Due to this year’s freshness, shark and ray counts are still well below average.

4. Advanced Anchovy Color Studies.

Yellowfin Gobies (left) and Northern Anchovies (right) in Pond A19 on 1 July 2023.

Anchovy count = 182. Anchovies are still recovering from the big freshwater flush of last winter. The good news is that they appear to be recovering quickly. In comparison, it took them almost three years to recover after the big flush of 2017.

- Hopefully, this is a sign that the local population, or perhaps the local spawning habitat, has grown more resilient against inter-annual atmospheric upsets.

Golden and green Anchovies side-by-side at Alv3 – They are actually expressing the same green hue after adjusting the light angle. A Shiner Surfperch is shown at bottom left.

Anchovy dorsal color has long been a mystery to me. All Clupeiform fishes appear to follow the same “Salinity-Induced Color Change” rule: They ‘blue up’ in high salinity (at or above roughly 19 ppt), and they ‘brown down’ in low salinity (at about 10 ppt or less).

- Previous bucket experiments showed that the full-color transition from blue to brown takes about 3 minutes for Shad, Herring, and Anchovies. (Sardines have not been bucket tested.)

- Potentially stress-inducing bucket tests are no longer performed on these fragile fishes. (There is no need.) Instead, investigation continues via brief observation and photography prior to release.

Green Anchovies showing variable amounts of color at different angles.

Light angle demonstration #1 – Station Alv3. Salinity was 13.8 ppt. This is near the low end of the green color range for Clupeiforms.

- All three Anchovies appeared either greenish or colorless/brownish depending on light angle.

The difficulty with Anchovies is that they don’t reliably follow the rules.

- For one thing, Anchovies lose the colorful iridescence on their dorsum as salinity drops. That does not happen in Herring, Shad, and Sardines.

- With the loss of iridescent guanine crystals, Anchovy dorsal color becomes weaker. The angle of illumination becomes critical. After the loss of most iridescence, an otherwise blue or green Anchovy can easily appear brown/colorless if the illumination and/or viewing angle is wrong.

Green and golden Anchovies in Pond A21. Again, all show the same greenish hue when light angles are adjusted.

Light angle demonstration #2 – Pond A21. Salinity was 13.3 ppt; just above the green-to-golden threshold.

- One Anchovy appeared green, and the other appeared golden/mostly clear.

- As each fish was rotated with respect to the illuminating sunlight, both fish expressed the same golden-green hue.

Golden Anchovies (essentially colorless) at upstream stations.

Light angle demonstration #3 – Dump Slough and Pond A19. Salinity was 6.9 ppt or lower at these two stations. This well below the “brown threshold” for Clupeiforms. All Anchovies appeared colorless or golden regardless of light angle.

- At such low salinity most Anchovies had completely lost all iridescence. Only a few still retained a small band of guanine that could be seen as a bright golden streak along the lateral line.

- Viewing angle becomes almost irrelevant at low salinity and near total loss of guanine crystals.

Blue Anchovies in the deeper and saltier Lower South Bay to the north.

Anchovies are always bluest in the saltier deep Bay. They also tend to retain more guanine crystals in their chromatophores so the hue is more easily seen from a wider range of angles.

- Iridescence explained. How Nature Makes Beauty With Physics https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wK7XjHbt4Z0

A blue-green Anchovy at LSB2. Two other Anchovies are faded – Blue color cannot be seen from this angle.

Important Note: In addition to the loss of guanine/light angle problem, Anchovies occasionally express the wrong hue for a given salinity. For some reason, Anchovies were particularly well-behaved on this July weekend and no outliers were observed. This will not always be the case, and it still remains part of the Anchovy mystery. – Investigation continues!

5. A Few Other Silvery Fishes.

Pacific Herring count = 1. This is probably the last young Herring we will see until next winter. Like Anchovies, a substantial portion of the Herring population spawns and hatches in the Bay.

- This young one is now big enough to migrate to deeper Bay water and eventually out to sea — assuming he doesn’t get eaten along the way.

- Also like an Anchovy, his dorsum will ‘blue up’ and his sides ‘silver up’ as salinity increases during his travels into clearer and darker seawater.

Rainwater Killifish count = 6. These extremely hardy East Coast non-natives tend to hug the shores, so we only ever catch a few that stray into the main stems of sloughs or creeks.

- The Rainwater Killifish is a decent mosquito fish. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rainwater_killifish

Another non-native killifish to watch for. Richard, a volunteer at a recent Lake Merrit bio-blitz event, alerted me that we need to be watching for Bluefin Killifish. Bluefins invaded Central California and Delta waters several years ago.

- USFWS 2018. Bluefin Killifish (Lucania goodei) Ecological Risk Screening Summary https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Ecological-Risk-Screening-Summary-Bluefin-Killifish.pdf

- Mahardja et al (2020) Introduction of Bluefin Killifish Lucania goodei into the Sacramento-San Jaoquin Delta https://escholarship.org/uc/item/855742qk

- Bluefin Killifish are sold as freshwater pond and aquarium fish: https://www.amazon.com/KOOL-TOOLS-Killifish-Aquarium-Mosquito/dp/B079KL52T8

6. Bugs

Bug Counts.

Mossy Byrozoan. We don’t actually count these soft coral-like colonies – we just note them. These mossy balls tend to form at stations Alv1 and UCoy2 around mid-to-late summer. Like soft-corals, they filter microscopic particles (animals) from the flowing freshwater river streams. They play an interesting role in local carbon sequestration.

Corbula Clam count = 281. Good News: low salinity seems to have hammered Corbula populations pretty well so far.

Musculista mussel count = 88. Despite finding many dead shells throughout the low-salinity spring, Musculista are bouncing back. 2022 was our record year for this non-native invader – also known as the “Asian Date Mussel.” We could be on track for another record.

Palaemon Shrimp count = 2716. We counted record numbers of non-native Palaemon shrimp during each of the last two drought years. Fortunately, this year’s count is much lower so far.

Crangon Shrimp count = 6300. Rainwater flushing aids Crangon recruitment. The year-to-date Crangon count is almost 27,000. So far, this is a good year, but 2023 is not likely to be a record-breaker.

Dungeness Crab, LSB1, 2 July 2023. – One young Dungeness was caught in July. These crabs rarely venture this far south in SF Bay.

Sami contemplates a tray of Crangon Shrimp at station Coy3.

California Gulls escorted us off the premises, and kept an eye out for another donut, at the end of the trawling weekend on 2 July.

California Gulls escorted us off the premises, and kept an eye out for another donut, at the end of the trawling weekend on 2 July.

Next Post

Next Post