Fish in the Bay – August 2023, Starry, Starry Summer!

The big story for August is that another 464 baby Starries were caught. When added to all the Starries caught since January, that makes a total of 1,260 for 2023 so far. I felt inspired to photoshop my own interpretation of Van Gogh’s famous painting.

Other interpretations of “The Starry Night.”

- Historical interpretation: Vincent Van Gogh’s The Starry Night: Great Art Explained https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wk9L1N9bRRE

- Musical interpretation: Don McLean – Vincent, The Story Behind The Song https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eTGcyuEU6Wo

- Scientific interpretation: Neil deGrasse Tyson on Van Gogh’s “Starry Night” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0nBMyj-r92A

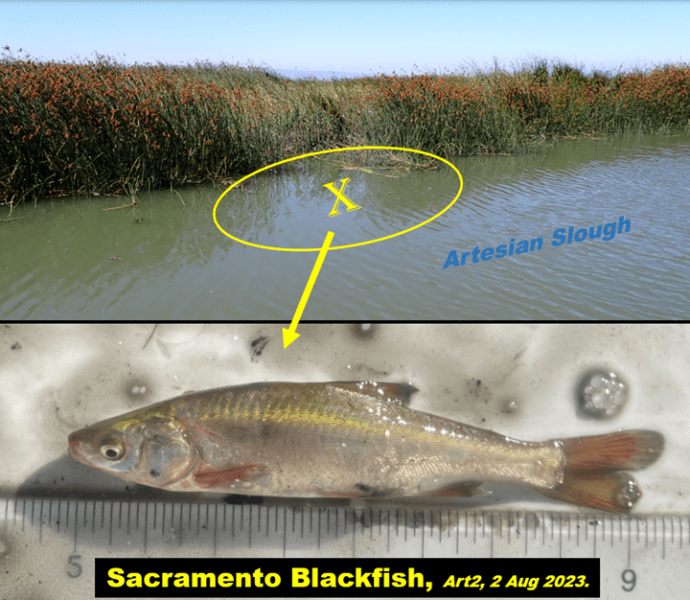

Artesian Slough was number one! More than half of this month’s Starries, most of the Shimofuri Gobies, all Silversides, Rainwater Killifish, and Prickly Sculpin, along with two oddball Carp, a Sacramento Sucker, and a rare Sacramento Blackfish were caught in Artesian Slough on the 12th.

This happens most summers as natural freshwater creeks dry up and marshes and sloughs get saltier. The San Jose-Santa Clara Regional Wastewater Facility discharges fresh tertiary-treated wastewater throughout the year. Many native and non-native fishes prefer fresher water when they can find it. For years, I have jokingly called this freshwater oasis “Sewer Plant Noah’s Ark.”

- “Sewer Plant Noah’s Ark is not entirely natural, but it certainly is attractive to many fishes. Look at the numbers!

Alviso Slough is the main freshwater source on the downstream side. Again, this is where most Shimofuri Gobies and all Prickly Sculpin were caught. Albeit we saw only one Inland Silverside and none of the other fresher water species.

1. The Year of the Starry.

Big Starry Year. In over 10 years of trawling, we have never seen so many Starries. And yet, Bay Study data and older surveys tell us that large Starry numbers like this might have been typical as recently as the 1980s.

Our Starries appear to have spawned in March or April. That might be a few months later than the typical Starry spawn, e.g. https://www.americanoceans.org/species/starry-flounder/

“Their spawning period runs from November to February. But they are most active during December through January, as they prefer colder water when fertilizing and reproducing. These fish do not usually lay eggs in deep water, sticking to the shores, riverbeds, and sloughs to keep their eggs safe from predators until they can hatch.”

Starry Flounder Growth Pattern in 2023:

- Seven Starries were caught between January and April. All were smallish, but still breeding-sized: between 120 to 195 mm standard length.

- Many baby Starries first showed up in May. All but a few measured between 15 to 50 mm.

- Baby Starries grew progressively larger each month. By August, most were ranging between 60 to 80 mm standard length.

Spatial Pattern: Baby Starries showed no particular spatial pattern from one month to the next.

- May – most Starries were caught upstream at stations Coy1, UCoy, Dmp, & Alv1

- June – most Starries were downstream at stations A21 & LSB1

- July – most were downstream at stations: Coy1, Coy2, Coy3, LSB1, & LSB2

- Aug – most were upstream at stations: Art2, Art3, UCoy, & Dmp.

What happened this year? We presume that abundant freshwater flushing from December through March aided Starry recruitment, but other factors must also have played a role.

- Continued attainment of Starry numbers like this would be an excellent restoration goal.

- We have no idea how this could be accomplished.

Great Egret fishing on the north bank of Coyote Creek near Coy1 on 12 August.

2. Bat Ray & Mud Ball Experience at Coy4

Sami and Micah carefully sieve young Bat Rays out of the muddy tub.

Bat Ray count = 9. We caught a cluster of very young Bat Rays at Coy4. They ranged in length from 175 to 290 mm. They were born close by within the last month or so judging from the sizes.

- Our trawl path drifted over part of a mud bank. The result was a big muddy mess to sift through.

- Sami and Micah quickly removed the Bat Rays before we started sifting. Bat Ray removal was the first priority. They can suffocate under the mud, and just as importantly, each one has a stinger. A frightened or angry Bat Ray can easily ruin your day.

Sami examines a male Bat Ray (190 mm) at Coy4.

These nine young ones bring the year-to-date count to only 18. 2023 continues to be our lowest Bat Ray year since 2014!

Part of the mud ball at Coy4.

After Bat Ray removal, it took us over an hour to sift through the mud and count critters. We found over 1700 Palaemon and Crangon shrimp, 1400 Musculista mussels, almost 600 Corbula clams, and various other fishes and interesting creatures in the muddy mess.

Because of the mud bank and resulting mud ball, the bivalve counts at Station Coy4 were a bit higher than normal.

The Musculista count at this single station was astronomical. To put it in perspective, we have counted less than 500 Musculista in all trawls since 2016. We must have encountered a very dense Musculista colony that is either new or has gone undetected until now.

Fish counts at Coy4 were otherwise normal compared to other stations, so the trawl was not unduly biased in that respect.

3. Bugs in August.

Crangon shrimp count = 4033. Good News! So far, Crangon counts have not crashed like they did the past few summers. The year-to-date total is 30,729, which is good. We have had only three better years: 2020, 2018, and 2014. We may see a few thousand more Crangon by December.

Palaemon shrimp count = 5400. We counted 16,094 non-native Palaemon so far this year. Fewer would be better. But, at least the number has dropped substantially compared to the 45,000 we caught in each of the two previous dry years.

Exopalaemon shrimp count = 211. Exopalaemon numbers suddenly jumped from a dozen or less each month to over 200 in August. All but a few of these fresher water shrimps were caught in Dump Slough or at UCoy1.

- Counterintuitively, the 2023 Exopalaemon total is the lowest we have seen since 2014. One would expect that freshwater and low salinity would cause the Exopalaemon population to explode. We can only speculate that intense flushing early in the year may have substantially washed them out. (Don’t worry these non-natives will recover!)

Mossy Bryozoan. More Mossy Bryozoan balls were picked up at Alv1. I find them very interesting. I am not sure why.

Corbula clam count = 825. Good News: Corbula numbers remain low compared to previous years. Most of this month’s tally came from station Coy4 alone where our trawl net bit into the mud bank. Most of the Corbula there were very tiny new recruits; nearly gravel-sized.

Philine bubble snail count = 5. Good News: Philine numbers have been low the past few years, and they continue to drop. These non-native gastropods are predators of other mollusks in Lower South Bay most of which are also non-native. (Philine probably eat baby Corbula clams, for example.) For that reason, I am not sure if the Philine impact is overall good or bad here. But, Philine are rather ugly to look at. We call them “Snot-Ball Snails” for a reason.

Tunicate count = 169. All Tunicates were picked up at LSB2 and nowhere else. Being filter feeders and fast bloomers, we expect Tunicate numbers to explode or shrink in response to phytoplankton food availability. So far, no huge explosion.

Musculista mussel count = 1636. Bad News: Musculista are on the move! This month’s count greatly exceeds all Musculista we have ever counted in ten years of trawling. As discussed above, almost 1400 of these little guys came from station Coy4 alone. However, even if we exclude the Coy4 mud-bank-blowout, the total would still set a new monthly record at 243. And, 2023 stands as our record Musculista year, with or without the Coy4 blowout.

- For better or for worse, Musculista consolidate the soft mud bottom by forming dense colonies held together by interlocking byssal threads. Are Musculista now here to stay? How will they change our bottom ecology? What eats them?

Kayakers glided downstream near Alv2 as we trawled. Greenness persisted here through August.

Green Water. We kept our eye on the water color throughout the weekend. Like everyone else in San Francisco Bay, we were on high alert for any signs of another H. akashiwo red tide event. Happily, we only saw green and greenish-brown water at all stations.

4. Fish That Like Fresher Water.

A Photarium full of Sticklebacks, Gobies, a Longjaw Mudsucker & a Rainwater Killifish at Art1 on 12 Aug.

Three-spined Stickleback count = 57. More than half of the Sticklebacks were caught in Artesian Slough in August. All but one were caught at upstream stations. Sticklebacks tolerate a wide range of salinity, but they clearly prefer low salinity.

- Sticklebacks inhabit estuaries and freshwater rivers and creeks all over the northern hemisphere.

- They are revered as starter aquarium fish in cultures from England to Japan. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three-spined_stickleback

- We named this one “Sticklezilla” because he was the largest Stickleback we have ever seen: 50 mm! That’s almost five Mysids long!

Inland/Mississippi Silverside count = 43. All but one Silverside was netted in Artesian Slough. Like the Stickleback, Silversides consume eggs and larvae of pelagic fishes. Unlike Sticklebacks, Silversides are non-native and are well-documented ecosystem killers in California.

- This fish always represents a severe threat to our Anchovy and Longfin Smelt spawns.

- Silversides should be controlled and eliminated with extreme prejudice. This is a very bad fish for California! https://californiawaterblog.com/2023/03/19/the-rapid-invasion-of-mississippi-silverside-in-california/

The Photarium at Art1, a second look.

Shimofuri Goby count = 898. As explained in the previous post, we experienced a huge Shimo blowout. This was the second biggest we have seen since October 2021 (997).

Starry Flounder, Silversides, Shimofuris, plus Anchovy & Common Carp at Art2 in August.

Prickly Sculpin count: 7. Pricklys are a sign of rainwater flushing. We tend to see more Pricklys after good rain.

- Pricklys are classic natives of San Francisco Bay and the Delta. From here they range north to British Columbia. https://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/acat/documents/r10789/8840209-App.A-Speciessummary-Sculpin_1188324989021_f6d9ed881f674be38a50ea8d31322657.pdf “Sculpins spawn in the early springtime, usually between March and June (Scott and Crossman, 1973) when water temperatures reach 10ºC (Coker et al, 2001). Males are the first to arrive on breeding grounds (Scott and Crossman, 1973), and guard a nest on the underside of small rocks, or other items (Scott and Crossman, 1973; Coker et al, 2001). Females move into spawning areas and deposit adhesive eggs on the undersides of the nest (Scott and Crossman, 1973). Males may court multiple females in the nest and as many as 30,000 eggs have been observed in a single nest (Scott and Crossman, 1973). Males guard eggs until they hatch, providing parental care by fanning the eggs to oxygenate them (Scott and Crossman, 1973).”

Sacramento Blackfish. On August 2nd, Sami, Micah, and the UC Davis crew pulled up a young California Blackfish by beach seine beneath a stand of California Bulrush near Station Art2 in Artesian Slough. — Because this was a separate beach seine mission, it is not included in the monthly trawl table.

Blackfish normally stay away from salty Bay water where we monitor.

- Sacramento blackfish according to UC Davis: https://calfish.ucdavis.edu/species/?uid=80&ds=241

- Sacramento Blackfish per WC Fisheries: https://www.wcfisheries.com/sacramento-blackfish

This adult Blackfish was caught near Alv1 in 2017.

We have only ever seen one Blackfish before: in February 2017, when big rains at that time made Lower South Bay as fresh as river water.

- The Blackfish is a very strange and highly edible California native. https://www.record-bee.com/2018/02/20/blackfish-often-mistaken-for-hitch-at-clear-lake/

Sacramento Sucker at Art2.

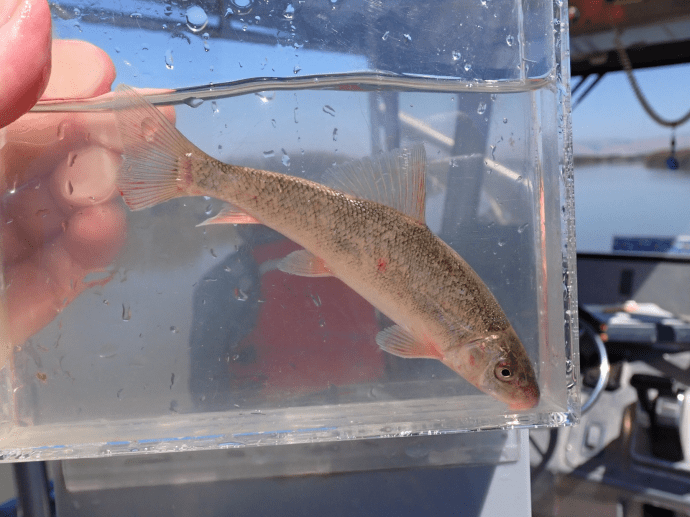

Sacramento Sucker. This is another native freshwater fish that we rarely see this far downstream. It is also the first we have ever caught in Artesian Slough.

- Suckers were important food fishes for Native Americans. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacramento_sucker

Common Carp at Art2.

Common Carp. Two Common Carp were caught; one each at Art1 and Art2. Carp are not native and not rare. They live in local rivers and even in the SJ-SC RWF freshwater outfall channel just upstream. However, they have never ventured this far downstream until now. These were the first Carp we have ever seen in regular monthly trawls.

- From Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eurasian_carp

Longjaw Mudsucker count = 14. Mudsuckers burrow into the muddy banks, usually where pickleweed grows. The trawl net catches stragglers that accidentally venture into the main channels. In August, we caught 11 in Artesian Slough and 3 in Dump Slough – Nowhere else!

- Literature says that Mudsuckers thrive when salinity is above 12 ppt. But ironically, all eleven Mudsuckers in August were caught in lower salinity. https://calfish.ucdavis.edu/species/?uid=49&ds=241

- Longjaw Mudsuckers can respire and survive out of water for at least 12 hours: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Longjaw_mudsucker

Dungeness Crab, Crangon Shrimp, & some Ceramium red algae at station Alv3 on 13 Aug 2023.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post