Fish in the Bay – January 2023, Part 1 – Atmospheric River Blowout.

Heavy cold rain drenched us on January 14th and 15th. We were under at least the sixth Atmospheric River that swept over Northern California since Christmas. Coyote Creek and Guadalupe River were swollen and beige-brown from all the sediment. It looked like we were floating on Café o’lait in all segments EXCEPT Artesian Slough, as explained below.

IT WAS CLEANUP TIME!!! Altogether, this was the first good scrubbing these rivers have experienced in at least 3 years, maybe much longer.

List of just-before-Christmas thru mid-January Atmospheric Rivers (in reverse order):

#6: 16 Jan 2023. Another storm lashes California after a barrage of brutal weather kills 19. … https://www.msn.com/en-us/weather/topstories/another-atmospheric-river-lashes-california-renewing-flooding-concerns-in-state-where-storms-have-left-at-least-19-dead/ar-AA16nYN3

#5 10 Jan 2023. California Atmospheric River Count: 5 Down, 4 to Go Before Jan. 19 “The deluge of rain soaking parts of California — including the Central Valley— came from the state’s fifth atmospheric river since Christmas, officials said Monday.” https://gvwire.com/2023/01/10/california-atmospheric-river-count-5-down-4-to-go-before-jan-19/

#4: 4 Jan 2023. “Just four days after heavy rain hit California, the state was drenched with another atmospheric river on January 4 and 5, 2023.” https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/150804/atmospheric-river-lashes-california

#3: 1 Jan 2023. NWS Bay Area: “Our San Francisco Downtown site hit 5.46” in the 24 hours of December 31st. This makes it the second wettest day in the 170+ years of records at that site, just 0.08” less than 1st place (11/5/1994) with 5.54” https://twitter.com/NWSBayArea/status/1609512724693934080

#2 28 Dec 2022. ‘Atmospheric river’ pounds California, Washington, Oregon with heavy rain, wind … https://www.foxnews.com/us/atmospheric-river-pounds-california-washington-oregon-heavy-rain-wind-thousands-lose-power

#1 20 Dec 2022. CW3E AR Update: A series of atmospheric rivers (ARs) is forecast … to make landfall along the West Coast of North America during 22-27 Dec. Per Fish et al (2019), these types of multi-AR events, known as “AR families,” are not uncommon during boreal winter. https://cw3e.ucsd.edu/cw3e-ar-update-20-december-2022-outlook/

- See Fish et al (2019). Atmospheric River Families: Definition and Associated Synoptic Conditions https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/hydr/20/10/jhm-d-18-0217_1.xml

According to Paul Rogers on January 17th: “From Dec. 26 to Jan.15, a total of 17 inches of rain fell in downtown San Francisco. That’s the second-wettest three-week period at any time in San Francisco’s recorded history since daily records began in 1849 during the Gold Rush … The only three-week period that was wetter in San Francisco… came during the Civil War, when a drowning 23.01 inches fell from Jan. 5 to Jan. 25, 1862, during a landmark winter that became known as “The Great Flood of 1862.” https://www.mercurynews.com/2023/01/17/california-storms-the-past-three-weeks-were-the-wettest-in-161-years-in-the-bay-area/

The Great Flood of 1862: https://www.sfchronicle.com/oursf/article/How-bad-was-California-s-Great-Flood-of-17711100.php

… BTW, Northern California was hit by at least two more Atmospheric Rivers later in January. We badly needed this rain.

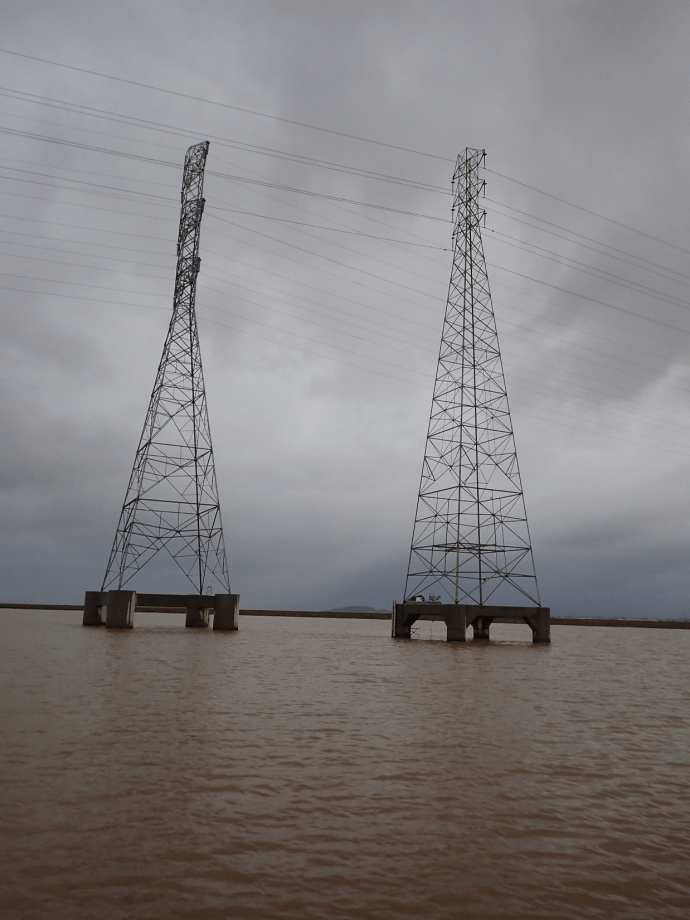

Alviso Marina at 8:00 AM on January 15th.

We were greeted by rain and very muddy waters when we commenced trawls on both trawling days in January.

Swollen muddy river at the confluence of Alviso Slough (Guadalupe River) with Coyote Creek – station Alv3.

We caught only 4 fishes in all of Alviso Slough (stations Alv1, Alv2, and Alv3). Instead, the net picked up big and heavy wads of bottom detritus at each station: heavier clam shell-hash at Alv1 and Alv2, and a big pile of shredded dead plant debris at Alv3.

Sediment and plant material washing down Coyote Creek on January 14th.

Overall fish counts were a bit low. The outgoing currents were strong. Heavy river flows likely (and hopefully only temporarily) washed out fish and bug populations to a large degree.

- Good News. 269 Longfin Smelt were caught. Many were big and showed signs of bearing eggs or milt.

- Threatened Longfins constituted our #1 fish in terms of weekend catch numbers (36% of all fish caught). The number two fish catch was a combination of gobies, principally the close cousin combination of Chameleon and Shimofuri gobies. American Shad were #3. Anchovies were #4.

- Unfortunately, English Sole and Staghorn Sculpin numbers were way low for whatever reason. Those are two of our main wintertime migrants. Hopefully, the numbers will improve.

A small contingent of the biggest Longfins were congregating far upstream where the brown water was freshest! UCoy1 was again a Longfin Smelt spawning ground!

1. Ducks!

Ducks over marshes west of Alviso Slough on January 15th.

As the saying goes, it was good weather for ducks. We could not identify species through the rain and obscurity, but Northern Shovelers, American Widgeon, Green-winged Teal, Ruddy Ducks, Buffleheads, Canvasbacks and several other species are commonly seen this time of year.

Ducks over Coyote Creek on January 14th.

I do not know if the duck population is higher this year, but it seems like we were seeing more of them along the Coyote Creek corridor.

2. Longfin Smelt: Lessons from the Spawning Ground.

Younger smaller Longfins at Coy3.

We found many smaller Longfins at the downstream locations: Coy 2, 3, and 4, and Pond A21.

Adult male (top) and female (bottom) longfins at Coy4.

As usual, the few adults we saw at downstream stations appeared to be well-fed and silvery.

Young Longfins at Coy2

The youngsters downstream seemed to be predominantly female as near as we can tell. Salinities were between roughly 2.5 to 6 ppt downstream, but the spawning adults, particularly the males, prefer fresher water far upstream.

The darkening. Adult Longfins turn progressively darker as they get ready to spawn in fresher water at upstream stations.

Slightly grayer male Longfin from Pond A19.

Levi Lewis recently informed me that male Longfins raised at the UC Davis Bodega Marine Lab (https://marinescience.ucdavis.edu/bml/about) stop eating when in spawning mode. They get skinnier and skinnier as they starve. We see the same thing here in Coyote Creek. Spawning appears to be a one-way trip for them – a suicide mission as near as we can tell. I was very sad to hear this.

As discussed in previous wintertime blogs, male longfins develop a pronounced ‘belly flap’ and long anal fin as they become ready for spawning. Each male uses his anal fin to clean a piece of hard or firm substrate as a nesting spot upon which to entice ready females to deposit eggs. … and then, he dies.

- Longfin Smelt are anadromous. Females can release thousands of sticky eggs over sand, gravel, rocks, or aquatic plants (Moyle 2002): https://wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/Fishes/Longfin-Smelt

- Fertilized eggs stick to the substrate and hatch after about 30 days. See: Paulinus Chigbu (2011) Population Biology of Longfin Smelt and Aspects of the Ecology of Other Major Planktivorous Fishes in Lake Washington “The duration of egg incubation for longfin smelt in Lake Washington is about 30 days (Moulton 1970).” https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/02705060.2000.9663777

Male Longfins show a pronounced belly flap and long anal fin. They also tend to look increasingly emaciated as spawning season progresses. In addition to not eating, males burn energy clearing and defending nesting sites.

Female Longfins feed and rest at downstream locations as they swell with developing eggs. When ready, females swim upstream to seek an attractive male – or maybe several. That’s the theory. (We don’t yet know for sure if any females might survive the spawning season to return next year.)

Closeup of two female Longfins at UCoy1.

Sami Araya showed me how he assesses the “stage” of reproductive readiness in female Longfins based on the appearance of their full bellies. He learned this trick from years of analytical observation at the UC Davis CABA lab. I have not yet mastered this technique.

The darkest Longfins are far upstream. Both male and female Longfins darken the longer they are in spawning mode at upstream stations. Males arrive first and spend the most time at the spawning ground, hence they tend to turn darkest.

Most Longfins caught at the UCoy1 spawning ground are males. They guard their nesting sites and wait for the arrival of ready females full of eggs.

3. Oddball Fishes and a Bug.

Pacific Lamprey. So far, only one young Lamprey was caught in 2023. We caught none in 2022, and I think 3 in 2021. (see Fish in the Bay, February 2021: https://www.ogfishlab.com/2021/02/14/fish-in-the-bay-february-2021-tales-from-the-coral-reef-and-the-spawning-ground/).

- Lampreys are very muscular boneless and jawless fish. They easily slip through the mesh in our net, so we very rarely catch them. All of the several we have caught in recent years have been young “macropthalmia-age” (aka “big-eye” age).

- They hatch and grow to this size in clean clear creek sediment for 5 to 7 years. We catch them on their migration out to sea in late winter to early spring. They will feed and grow big in the ocean for one to three years before returning to spawn and die.

- Lampreys are among the best signs of upstream creek health according to USFWS: “Pacific lamprey play an important role in West Coast rivers and streams as ecosystem engineers and food web champions. Several [Native American] tribes have historically considered Pacific lamprey a ‘first fish’ whose return signals the beginning of spring and summer harvests.” https://fws.gov/species/pacific-lamprey-entosphenus-tridentatus

Pacific Tomcod at Coy3

Pacific Tomcod. We caught 13 Tomcods from January through May 2022. This season, the count is 19 from December and January. Prior to that, we have only ever caught one or two.

For some reason, these common Cod-family bottom-dwellers from the coast have decided to migrate deep into Lower South Bay for a second year in a row. Why???

Mud Shrimp (Upogebia major) at LSB1

Upogebia, aka. Mud Shrimp. The Mud Shrimp story is a little long and complicated. You can find it here: https://www.ogfishlab.com/2022/01/01/fish-in-the-bay-january-2021-mud-shrimp-alert-upogebia-explosion-on-new-years-day/

TLDR: The shrimp shown here is the non-native Asian (Upogebia major) variety. We think this is our ‘new native’ that has displaced the native Upogebia pugettensis at least a decade ago. The good news is that either type of Mud Shrimp is highly beneficial in the brackish marshes. They are ecosystem engineers that bioturbate and oxygenate the soils by building arcades of deep burrows amongst plant roots and rhizomes. Upogebia burrows also provide habitat for other organisms. – Upogebia are also a favorite food for White Sturgeon. So, that is another plus.

The mystery is: Why do we occasionally catch these deep-burrowing little lobsters outside of their burrows? As far as we know, adult Upogebia cannot dig a new burrow and they are defenseless out in the open. Freshwater flushing we experienced in early January was huge, but still probably not enough to have dislodged this one from its hole. What is going on here?

We notified Dr. John Chapman at Oregon State University about this latest specimen. He is the Upogebia expert. We will continue to ponder this mystery.

Every fish and bug tells a story.

It reminds me of an old rocking Rod Stewart tune:

(Warning culturally-insensitive lyric in part of this song!)

“I couldn’t quote you no Dickens, Shelley or Keats

‘Cause it’s all been said before

Make the best of the bad, just laugh it off

You didn’t have to come here anyway

So remember, every picture tells a story, don’t it

Every picture tells a story, don’t it

Every picture tells a story, don’t it … etc.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T9GapvypdEo

to be continued …

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post