Fish in the Bay – January 2023, Part 2 – The Rest of the Fishes.

Part 2 of the January report covers all the other interesting fishes and bugs.

Seven atmospheric river storms that swept through during the three preceding weeks turned the water fresh and turbid. Strong flushing river currents pushed sediment, detritus, and small critters downstream. Consequently, overall fish and bug numbers were a bit low as most of the populations were either blown out or had retreated away from the main channels to sheltered areas.

This big freshwater flush is ultimately very encouraging for several species, like Longfin Smelt, American Shad, English Sole – and YOUNG Crangon Shrimp, that seek cold freshwater for spawning or recruitment. But, at the same time, an abrupt freshwater flush like this one can be deadly for Leopard Sharks, Bat Rays, Anchovies, and ADULT Crangon Shrimp. All of the latter must flee Lower South Bay or die.

1. Pelagic Fishes.

American Shad, Longfin Smelt, and two Anchovies from Dump Slough.

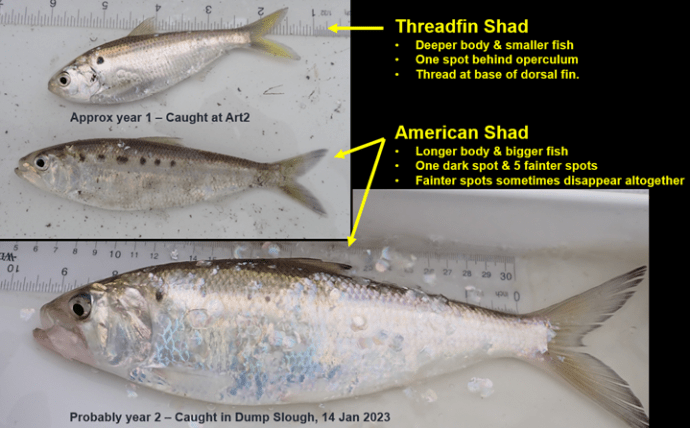

American Shad and Threadfin Shad. 197 American and 19 Threadfin Shad were caught in January. It was a good total, but we did catch more in Januarys of 2018 and 2019. Intervening drought years knocked their populations back a bit.

American Shad swim upstream to the big Central Valley rivers to spawn. However, we only ever see very young shad here in Lower South Bay. These are between one or two years old.

American Shad and Threadfin Shad were both introduced to California from the East Coast in the late 1800s.

- Threadfins are smaller cousins of the Americans. They grow to roughly five inches in length.

- American Shad usually grow to about 20 inches, but some can get bigger.

- BTW: American Shad & Pacific Herring look very similar and can easily be confused. Always run your finger, from tail toward head, along the underside. Herring have soft bottom scales. The bottom scales on Shad are hard and spiky. Some people refer to Shad as “Saw-Bellies” for that reason.

Adult Anchovies at Coy3

Northern Anchovies. More than half the 58 Anchovies caught in January were larval or very young juveniles between 30 and 60 days old.

A smaller portion were adults, like those shown here. Northern Anchovies easily tolerate salinity as low as 10 ppt, but probably don’t tolerate much lower than that. Not surprisingly, almost all Anchovies were far downstream. Almost half were caught at LSB stations.

Larval and juvenile Anchovies at LSB2

2. Other Fishes.

Three English Sole and two Speckled Sanddabs at LSB.

English Sole and Speckled Sanddabs. All the 14 English Sole, and all but two of the 24 Sanddabs, were caught far out in the Bay at LSB stations.

Flatfish identification: All of the various flatfishes we catch are easy to identify as adults, but it gets tricky for the younger ones. For English Sole versus Sanddabs, eye orientation is one key: English Sole eyes are always on the right side of the head – left of the mouth (aka. right-eyed). Sanddabs are always left-eyed.

Juvenile Anchovy and a tiny “unidentified” baby flatfish at LSB1.

Baby fishes in the fish nursery. We usually see near-larval Anchovies and flatfishes of various species this time of year. Some are too small to be identified.

What is this near-larval flatfish shown above?

- the lateral line does not show a sharp upward bending curve behind the operculum – NOT a halibut,

- there is no trace of light and dark coloration on fringing dorsal and ventral fins – MAYBE NOT a Starry Flounder, and

- the fish is right-eyed, so it is LIKELY an English Sole.

Starry Flounder at UCoy1.

Starry Flounder. Young Starries return to spawn in late fall through winter at the foot of creeks after their first year. Flushing rivers deposit organic material that feeds the food web upon which they depend.

- The last few drought years reduced local Starry numbers considerably. Hopefully, this year’s big flush will bring us some good Starry recruitment.

A mix of Shimofuri and Chameleon Gobies at LSB1.

Shimofuri and Chameleon Gobies. Shimos and Chameleons are very close cousins. Some studies suggest that they easily interbreed. Shimos are native to brackish estuarine waters in Japan. Chameleons live closer to the ocean at higher salinity.

- Extra freshness from rainwater flushing pushes the Shimofuris farther out toward LSB stations each winter, and we end up seeing an interesting mix of both types there.

Bay Pipefish. The five pipefish caught this month were all adults. At least three females and one male showed clear signs of reproductive readiness. Or, more likely, they had just finished the brooding and birthing process.

- This Wikipedia article gives a good description of Pipefish reproduction: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pipefish

3. Invertebrates.

Only one egg-bearing Crangon at Coy4

Crangon Shrimp. The native Crangon catch continues to be a bit disappointing; not horrible like it was in 2015 and 2016, but not as excellent as it was in 2018 and 2019. In good years, we caught thousands of egg-brooding females in December through February. This year, we caught only one or two!

- Crangon franciscorum females (the brown tail variety) swim as far upstream as they can tolerate in winter. The adults don’t like salinity much below about 20 ppt. (Note: Some literature conflicts with our Lower South Bay observations regarding the Crangon brooding migration. More discussion about this at some later time.)

- They release their brood as it hatches. From that point on, the tiny babies swim and drift farther upstream into much fresher brackish water where they can more safely recruit.

- The last few drought years hammered the local Crangon population hard. And, now the strong pulse of freshwater flushing is probably keeping most adult females farther out in the deep Bay.

Three types of Crangon: Blue-spot, black tail, and brown tail.

Crangon nigricauda (black tail) and C. nigromaculata (blue spot). Black tail and Blue spot Crangon are the more marine-oriented cousins of C. franciscorum (brown tail). As usual, we only saw these two types at the farthest LSB station. Given the low salinity, I was surprised to see them at all.

Young Crangon recruits in Dump Slough on 14 January.

Good News. At least some Crangon recruitment is happening! We spotted small ones at several stations. Young Crangon don’t mind fresher water, in fact, they migrate to it soon after hatch.

There is considerable evidence that C. franciscorum are “protandrous hermaphrodites:” They spend their first year as males before transitioning to female in the second or third year. Robust rain this year will help these baby boy Crangon grow in into big mamas next year or the year after! https://oimb.uoregon.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/C_franciscorum_2018.pdf

Salinity at the mouth of Guadalupe River (station Alv3) was only 1.1 ppt on Saturday. Strong river currents churned up piles of shell hash and plant debris. The low salinity probably spelled doom for the Musculista mussels and small Anemones we found here. They can’t tolerate such low salinity for long.

Scale Worms are a much more marine species. The Scale Worm shown here probably got stuck in the net from the previous trawl at LSB2. In tide pools and shallow waters along the seacoasts, Scale Worms are among the most common invertebrates found.

In addition to Corbula Clams, we found one new clam that we are not familiar with at Alv1. Does anyone know this clam at top left?

We also spotted two California Horn Snail shells at Alv1. This is the native snail that has been all but extirpated from this part of the Bay in recent decades. It would be very fascinating if a surviving Horn Snail colony still survives along the Guadalupe.

- One of the two Horn Snail shells was definitely dead.

- The other looked like it may have still been alive. Only by cracking the shell could we be certain. We swallowed our curiosity and released the snail.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post